PFC WALTER E. BABCOCK

On June 6, 1944 (D-Day), the beginning of the end of the Atlantic part of World War II began with the invasion of Normandy. The successful invasion on the northern coast of France was a very complicated and deadly operation. When completed, it allowed the allies to establish a foothold from which they could strike out and drive the German army from Northern Europe back to Germany. The seizure of Normandy was far from the end of the operation. The rest of the job required a huge force to chase the German army back to Germany. The force would require that many allied soldiers put themselves in harm’s way. One of those soldiers was Walter Babcock of Springfield, South Dakota.

After spending some time at the University of South Dakota, including taking part in the ROTC program, Walter enlisted in the army at Fort Crook, Nebraska on September 22, 1943. He was trained as an infantryman at Camp Fannin in Texas. After his training, on April 7, 1944, he was shipped to England and the European theater of operations. In England, he joined a huge collection of soldiers and received further training preparing him for the invasion of the mainland. Walter sat out the Invasion of Normandy, but joined the legendary First Infantry Division (Big Red One) as a replacement a week later. Day 1 of the Invasion (D-Day) has received the majority of the attention over the years. Lost in all of the attention of day one was the intense combat required after D-Day to push the Germans back and establish a beachhead for the allies to operate from. Walter took part in the heavy battles to expand the Normandy beach heads and was wounded on August 9, 1944, taking him out of action.

While Walter recuperated, his division raced across France chasing the German army in a path through Mortain, to the Seine and then on to Soissons across the Alone River to Maubeuge, Charlero, Liege and Herve in Belgium. The resistance was light until they neared the German border where German resistance stiffened dramatically. At this point, Walter rejoined the battle on September 3.

During the first three days of Walter’s return, Walter’s division inflicted one of the costliest single defeats on the enemy in the Franco-Belgian campaign. In one five-hour period of fighting, Walter’s company killed or wounded 200 Germans, and captured 400 prisoners and much equipment. During the three days of fighting, the action was so intense and chaotic that there were no front lines. When the smoke had cleared, the defeat for the enemy was complete and The Big Red One and Walter moved on to the next objective.

The resistance was unexpectedly light as the First Division moved on to Aachen, a German border city incorporated into the Siegfried Line and a key German obstacle in the Allies goal of occupying the Ruhr industrial heartland. As they neared Aachen, resistance increased significantly. In Aachen, the fighting was bitter and moved to the south of the city where the Germans had concentrated their efforts. Walter’s 18th regiment seized 19 pillboxes in one action. The fighting centered on the American attempt to take Crucifix Hill and resorted to hand to hand fighting as Walter’s 18th regiment fought and absorbed attack after attack from German tanks, artillery, and infantry. The Americans fought off counterattacks and other desperate attempts by the Germans to change the momentum. As the Germans made their last efforts to defeat the Americans on October 19, Private Walter Babcock was tragically KIA in the desperate and ferocious fighting that took place to take Crucifix Hill. Two days later, Colonel Gerhard M. Wick, Wehrmacht commanding officer, surrendered unconditionally. Aachen was devastated with burst sewers, broken gas mains, bloated dead animals, shattered glass, dangling power lines and with no buildings remaining intact. It was the first city on German soil to be captured by the Allies and was the largest urban battle fought by US forces in WW II.

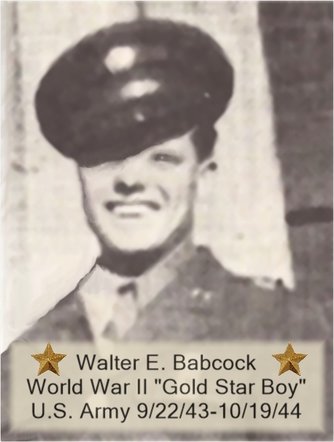

Memorial services were held for Walter Babcock on November 3, 1944 at the Springfield Congregational Church. He is buried in Europe at Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery at Plot C, Row 6, Grave 41. Private Walter E. Babcock was awarded the American Campaign Medal, the Combat Infantryman Badge, the WWII Victory Medal and two Purple Hearts. Walter’s death was a huge loss for Walter’s family and the town of Springfield. Many relatives and friends would only know Walter by his military picture, which was a picture of an engaging full of life confidant young man.

Dick Martin

After spending some time at the University of South Dakota, including taking part in the ROTC program, Walter enlisted in the army at Fort Crook, Nebraska on September 22, 1943. He was trained as an infantryman at Camp Fannin in Texas. After his training, on April 7, 1944, he was shipped to England and the European theater of operations. In England, he joined a huge collection of soldiers and received further training preparing him for the invasion of the mainland. Walter sat out the Invasion of Normandy, but joined the legendary First Infantry Division (Big Red One) as a replacement a week later. Day 1 of the Invasion (D-Day) has received the majority of the attention over the years. Lost in all of the attention of day one was the intense combat required after D-Day to push the Germans back and establish a beachhead for the allies to operate from. Walter took part in the heavy battles to expand the Normandy beach heads and was wounded on August 9, 1944, taking him out of action.

While Walter recuperated, his division raced across France chasing the German army in a path through Mortain, to the Seine and then on to Soissons across the Alone River to Maubeuge, Charlero, Liege and Herve in Belgium. The resistance was light until they neared the German border where German resistance stiffened dramatically. At this point, Walter rejoined the battle on September 3.

During the first three days of Walter’s return, Walter’s division inflicted one of the costliest single defeats on the enemy in the Franco-Belgian campaign. In one five-hour period of fighting, Walter’s company killed or wounded 200 Germans, and captured 400 prisoners and much equipment. During the three days of fighting, the action was so intense and chaotic that there were no front lines. When the smoke had cleared, the defeat for the enemy was complete and The Big Red One and Walter moved on to the next objective.

The resistance was unexpectedly light as the First Division moved on to Aachen, a German border city incorporated into the Siegfried Line and a key German obstacle in the Allies goal of occupying the Ruhr industrial heartland. As they neared Aachen, resistance increased significantly. In Aachen, the fighting was bitter and moved to the south of the city where the Germans had concentrated their efforts. Walter’s 18th regiment seized 19 pillboxes in one action. The fighting centered on the American attempt to take Crucifix Hill and resorted to hand to hand fighting as Walter’s 18th regiment fought and absorbed attack after attack from German tanks, artillery, and infantry. The Americans fought off counterattacks and other desperate attempts by the Germans to change the momentum. As the Germans made their last efforts to defeat the Americans on October 19, Private Walter Babcock was tragically KIA in the desperate and ferocious fighting that took place to take Crucifix Hill. Two days later, Colonel Gerhard M. Wick, Wehrmacht commanding officer, surrendered unconditionally. Aachen was devastated with burst sewers, broken gas mains, bloated dead animals, shattered glass, dangling power lines and with no buildings remaining intact. It was the first city on German soil to be captured by the Allies and was the largest urban battle fought by US forces in WW II.

Memorial services were held for Walter Babcock on November 3, 1944 at the Springfield Congregational Church. He is buried in Europe at Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery at Plot C, Row 6, Grave 41. Private Walter E. Babcock was awarded the American Campaign Medal, the Combat Infantryman Badge, the WWII Victory Medal and two Purple Hearts. Walter’s death was a huge loss for Walter’s family and the town of Springfield. Many relatives and friends would only know Walter by his military picture, which was a picture of an engaging full of life confidant young man.

Dick Martin