|

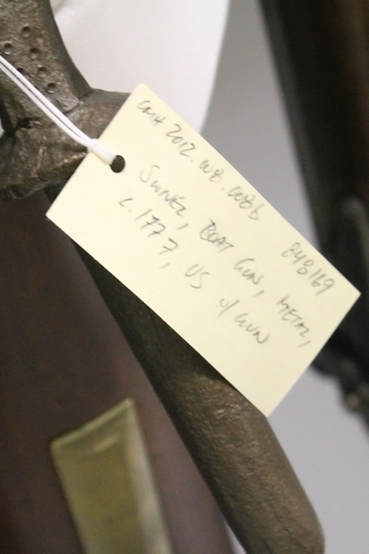

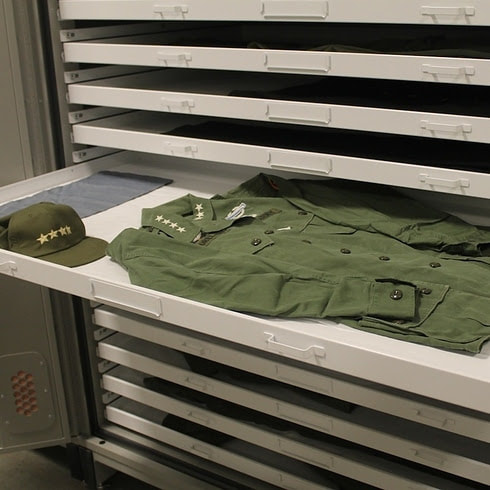

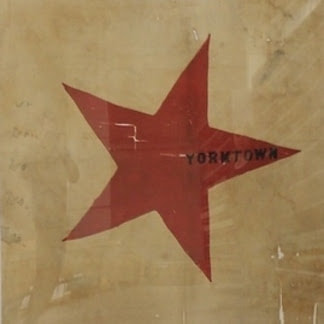

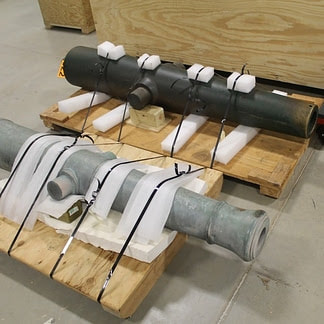

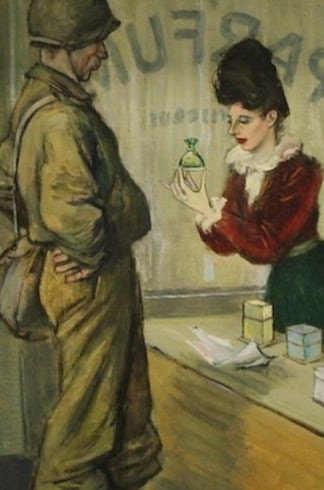

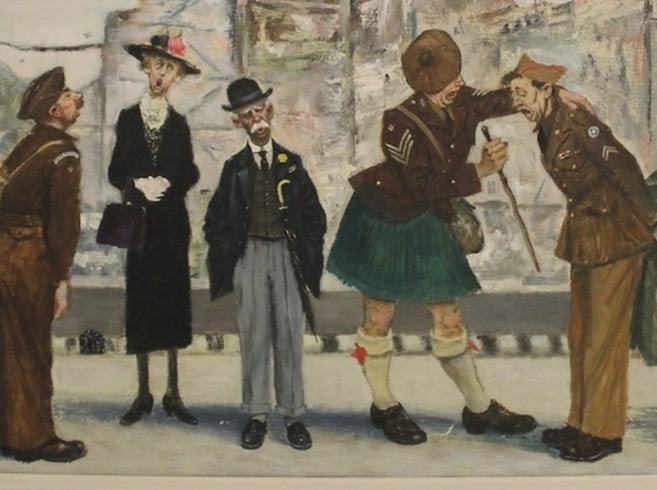

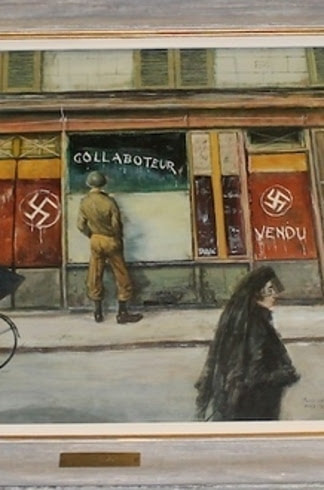

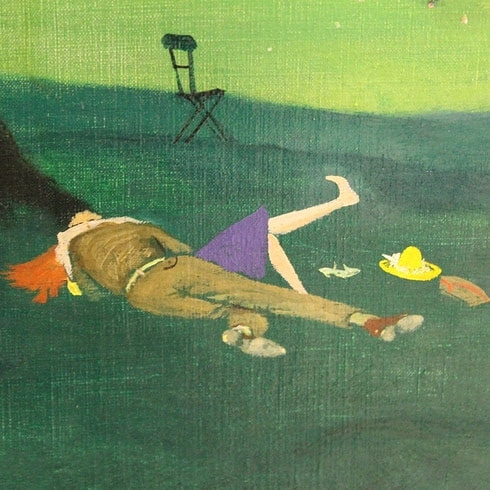

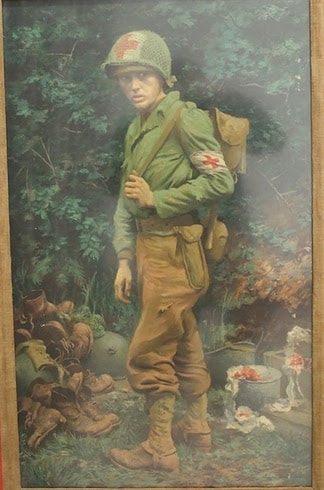

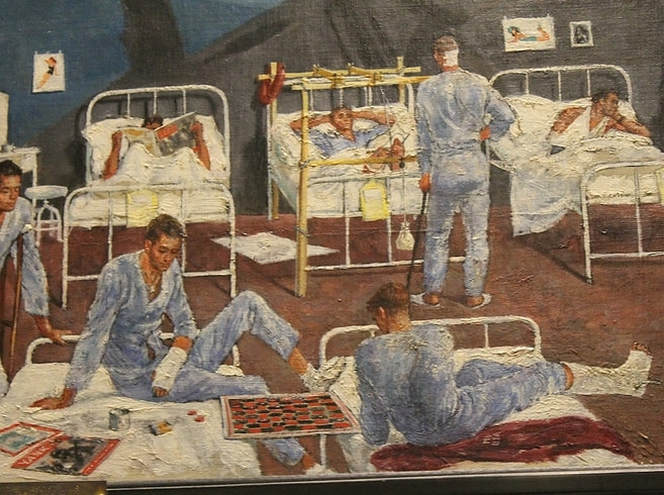

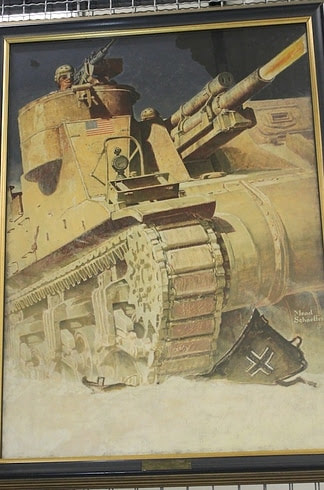

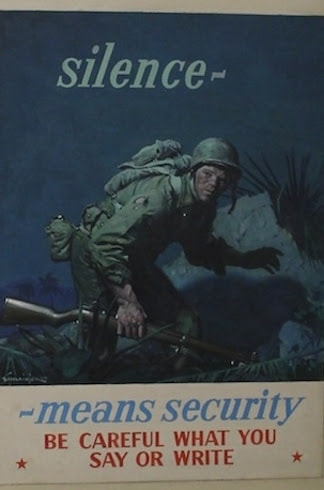

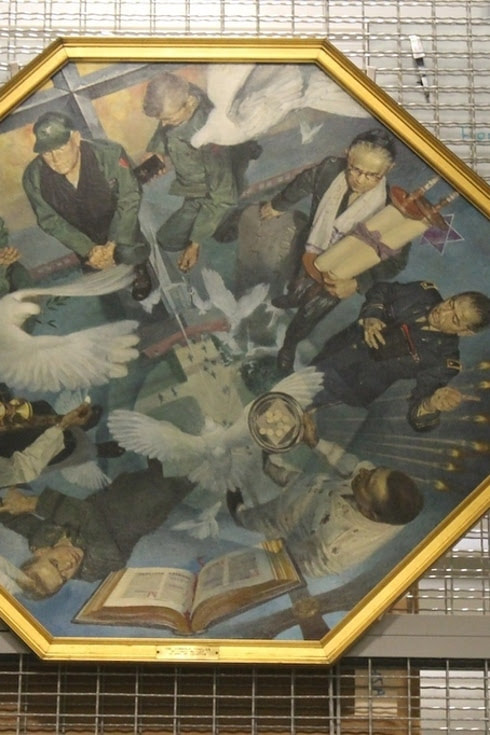

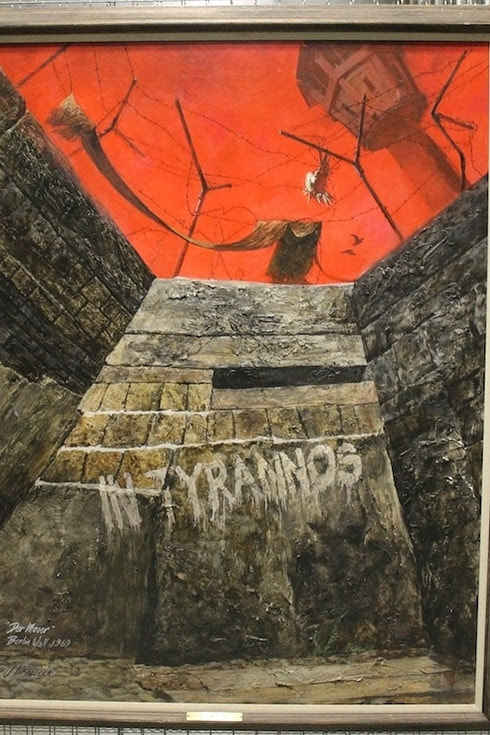

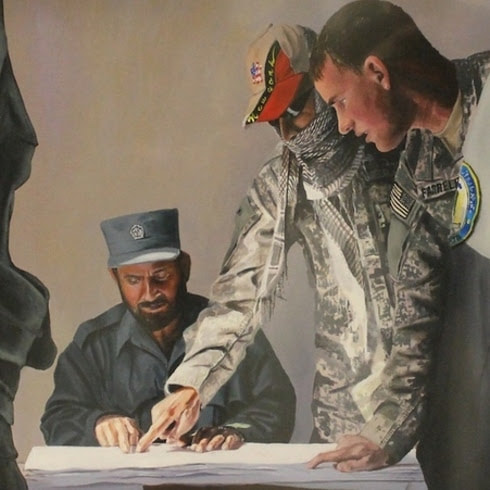

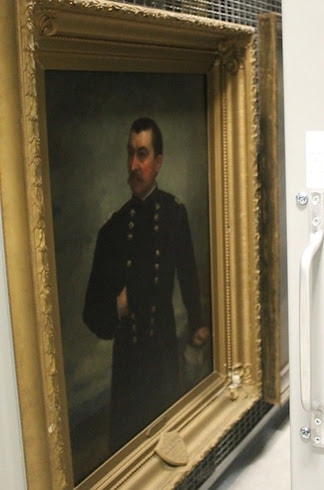

Submitted by Perry Lundin Remember that ending scene out of Indiana Jones where the Ark of the Covenant is boxed up and wheeled through an endless government warehouse? Did you know that that place actually exists? It is called the Center of Military History. It is located 30 minutes outside Washington, D.C., at Fort Belvoir in Virginia. The building itself is very nondescript… …but behind a series of highly alarmed doors… …and long, cement, camera-laden hallways… …is the highly sophisticated, climate-controlled treasure room where the Army keeps its most precious artifacts. The facility was built for $24 million in 2010. The cavernous warehouse is typically shrouded in total darkness. Motion lights illuminate only the areas in which someone is walking. Behind these giant doors lie the Army’s historic collection of weaponry. The room consists of dozens of collapsable “hallways” filled with the richest American firearm collection on the planet. The collection is stacked with priceless items. One-of-a-kind boat gun that pre-dates the Revolutionary War. The entire collection can be moved at the press of a button… …to create new endless hallways of historic firearms. Entire lineages of weapons are kept here for research as well as preservation purposes. Another portion of the warehouse consists of endless rows of gigantic airtight lockers. This is called “3D storage.” Every meaningful artifact that has been worn on a military battlefield is stored here. Including Gen. Ulysses Grant’s Civil War cap. Famous generals’ uniforms and Revolutionary War powder satchels… …flags, canteens, and cannons. And the rows go on and on and on and on… But the crown jewel of the collection is the 16,000 pieces of fine art the Army owns. The art is kept on giant rolling metal frames. The massive collection consists of donated and commissioned pieces. Much of the art was painted by soldiers who experienced their subjects in real life. During World War I, the Army began commissioning artists to deploy into the war zone and paint the scenes they observed. This practice has continued to this day. Much of the museum’s collection consists of these commissioned wartime pieces. The collection also keeps hold of valuable donated military art and historical pieces dating back to the Mexican American War. The art tells the story of America’s wars through a soldier’s unique perspective. Some works are just beautiful beyond words. “Softball Game in Hyde Park” by Floyd Davis. Every aspect of war is captured in the collection. The collection also includes original Army propaganda art. Including beautiful Norman Rockwell originals that the Army commissioned in the 1940s. Original Rockwells like these regularly fetch tens of millions of dollars at auction. Virtually every American conflict is represented from a first-hand soldier’s perspective. VIETNAM DESERT STORM Humanitarian aid missions to the conflicts of the 1980s: PEACE AND WAR The “War on Terror.” The soldier’s perspective… The collection also has a controversial side that has never been displayed. Unique art and artifacts that were seized from the Nazis after World War II are stored here, including watercolors painted by Hitler himself. The painting below was filmed at the center for the 2006 documentary The Rape of Europa. At the age of 18, Adolf Hitler applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna but was rejected. A number of Hitler’s paintings were seized by the U.S. Army at the end of World War II and found a home at the center. None of the confiscated Nazi art has ever been displayed, and the curators thought them too controversial for this piece. Not a single piece in this massive collection is open to the public. Why is it kept under lock and key in a blackened warehouse? Simple answer: Because there is no museum to house it. The entire collection could be made accessible to the public, if the funds for a museum could be raised. The Army Historical Foundation is in charge of raising the funds for the museum via armyhistory.org However, there are major fundraising hurdles to jump before the museum can be built. The foundation’s president recently told The Washington Post that it has raised $76 million of the $175 million required for the museum and predicts the museum could open in 2018. The plan is to build the museum at Fort Belvoir. But until then…

0 Comments

Submitted by Daryl Heusinkveld

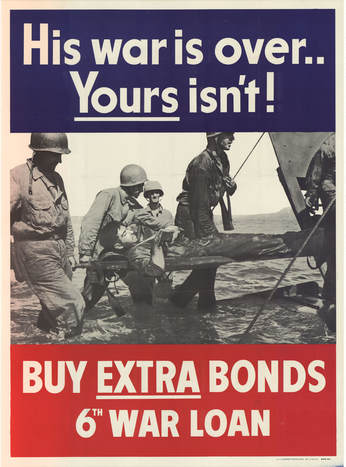

Academy Award-nominated documentary, which shows the 21st Bombing Command and its role in the B-29 bombing of Japan and the Pacific Theater of Operations. Either click on the link below or copy and paste in your browser. https://archive.org/details/TheLastBomb1945 Submitted by Dick Martin Here is clipping from the Springfield Times in November of 1944:  Our War With Japan The Sixth War Loan marks a new turn in the war both on the fighting and the home fronts. It points our tremendous war effort definitely in the direction of the Pacific. During the first five war loans Americans were primarily thinking in terms of beating Hitler. Now our government asks us for a loan of 14 billion more dollars of which five billion dollars must come from individuals. Why? Haven’t we nearly finished off our so-called Number 1 Enemy? Can Japan hold up our powerful war machine very long? Your son, brother and friend in his Pacific foxhole wouldn’t raise such questions because they are up against realities, not day dreams. They kill or are killed. They pray every waking moment for a sky-darkening cover of friendly plane. They thank America for giving them the finest medical care in the world when their rendezvous with destiny in a Pacific jungle is at hand. They know the war with the Japs is just beginning. Here are some other Pacific realities so that you will understand why there must be a Sixth War Loan and why it is absolutely necessary that it be a success: The Allied Military Command has estimated that it will take years, not months, to lick Japan. Japan’s present army numbers about 4,000,000 with 2,000,000 more men available and fit for military service who haven’t been called up to date. Another 1,500,000, between the ages of 17 and 20, are not yet subject to the draft. The Jap Air Force is growing. In addition to millions of native workers, Japan has a potential slave force of 400,000,000 conquered people. 50% of Japan’s labor force is made up of women. Another 25% boys and girls under 20, the balance men. The Jap workday is twelve to sixteen hours with two days off a month. The Jap cannot leave his job, change it, or strike. The highest daily wage equals about three American dollars—30% to 75% of which goes to taxes and compulsory savings. The Jap, as our men in the Pacific know, will fight to the death. As far as the Jap is concerned, the outer Empire—and the men who defend it—are the expendables. The Jap will fight the Battle from inside the inner Empire. The Jap believes that we shall weary of war too easily and too early. In the invasion of France, supply ships had an overnight run to make. In the coming Battle of Japan, ships in the Pacific will have long-reached round trips that often take five months to make. These realities are worth thinking about before you keep your home front rendezvous with a Victory Volunteer. Perhaps you will feel that the national personal Sixth War Loan objective—purchase of at least one extra $100 War Bond— is entirely too small for you. Submitted by Jim Hornstra Retired Marine Ronald L. Ridgeway was 18 years old in 1968 when his patrol was attacked in Vietnam. He was captured and held prisoner for five years before being released, a time during which he was believed dead. (Matthew Busch for The Washington Post) HALLETTSVILLE, Tex. — Ronald L. Ridgeway was “killed” in Vietnam on Feb. 25, 1968. The 18-year-old Marine Corps private first class fell with a bullet to the shoulder during a savage firefight with the enemy outside Khe Sanh. Dozens of Marines, from what came to be called “the ghost patrol,” perished there. At first, Ridgeway was listed as missing in action. Back home in Texas, his old school, Sam Houston High, made an announcement over the intercom. But his mother, Mildred, had a letter from his commanding officer saying there was little hope. And that August, she received a “deeply regret” telegram from the Marines saying he was dead. On Sept. 10, he was buried in a national cemetery in St. Louis. A tombstone bearing his name and the names of eight others missing from the battle was erected over the grave. His mother went home with a folded American flag. But as his comrades and family mourned, Ron Ridgeway sat in harsh North Vietnamese prisons for five years, often in solitary confinement, mentally at war with his captors and fighting for a life that was technically over. Last month, almost 50 years after his supposed demise, Ridgeway, 68, a retired supervisor with Veterans Affairs, sat in his home here and recounted for the first time in detail one of the most remarkable stories of the Vietnam War. As the United States marks a half-century since the height of the war in 1967 and ’68, his “back-from-the-dead” saga is that of a young man’s perseverance through combat, imprisonment and abuse. A 1973 photograph of Ridgeway after his return to the United States. (Matthew Busch for The Washington Post) He was 17 when he signed up with the Marines in 1967. He was 18 when he was captured, 19 when his funeral was held and 23 when he was released from prison in 1973. “You have to be willing to take it a day at a time,” he said. “You have to set in your mind that you’re going to survive. You have to believe that they are not going to defeat you, that you’re going to win.” ‘Everybody’s dead’ About 9:30 on the morning of Feb. 25, Pfc. Ridgeway’s four-man fire team charged an enemy trench line. The curving trench seemed empty when they got there. But as Ridgeway and the others made their way along it, suddenly an enemy grenade dropped in. “We back around the curve,” he recalled. “It blows up.” “We throw a couple grenades,” he said. “We backed off. . . . Then we realized the firing [from Marines] behind us had almost died down to nothing.” When they stood up to look around, they saw North Vietnamese soldiers walking through the underbrush toward them. “I guess they thought we were all dead,” he said. “We cut loose on them,” he recalled. “They were easy targets.” Ridgeway had been part of a platoon of about 45 men sent out from the besieged Khe Sanh combat base, in what was then northern South Vietnam, to find enemy positions, and perhaps capture a prisoner. The enemy’s noose around the Marine base had been tightening, with heavy mortar and artillery fire, and the patrol was hazardous. Six thousand Americans were surrounded by 20,000 to 40,000 North Vietnamese soldiers. On that foggy morning, the patrol’s leader, 2nd Lt. Donald Jacques, 20, strayed off course and was drawn into a deadly ambush, Jacques’s company commander, Capt. Kenneth W. Pipes, said. More than two dozen Marines, including Jacques, were killed. One of the Marines in the trench with Ridgeway, James R. Bruder, 18, of Allentown, Pa., was cut down as the enemy returned fire, according to author Ray Stubbe’s book about Khe Sanh, “Battalion of Kings.” “Stitched him across the chest and killed him,” Ridgeway remembered. The fire team leader, Charles G. Geller, 20, of East St. Louis, Ill., took a peek, and a bullet creased his forehead, knocking him down. “Everybody’s dead,” Geller said, according to Stubbe’s book. “Everybody behind us is dead. . . . What are we going to do?” They had to retreat. Geller left first, running back across the field where they had charged, followed by Ridgeway. The son of a Southern Pacific railroad worker, Ridgeway came from a working-class neighborhood of Houston. He had a younger brother. His parents were divorced. He had left high school and joined the Marines because “I wanted to get away,” he recalled. As he and Geller ran to the rear, they came upon Willie J. Ruff, 20, of Columbia, S.C., who was lying on his back with a broken arm. “We were in a hurry,” Ridgeway said. “But we stopped. He was wounded.” As Geller knelt beside Ruff, a bullet hit Geller in the face, leaving a terrible wound. Then Ridgeway was struck by a round that went through his shoulder. All three men were now down. “All we could do was lay there and play dead,” he said. “We were in the wide open.” Ridgeway said he drifted in and out of consciousness. When Geller, who was delirious, got to his knees, the enemy threw a grenade, killing him. Ridgeway said the North Vietnamese then began shooting at Marines who had fallen in front of their trenches. “They’re popping the bodies to make sure they’re dead,” he said. One bullet hit the dirt near him. A second glanced off his helmet and struck him in the buttock, he said. “When that hit, it jarred the body,” he said. “They figured they got me. Left me for dead and kept working their way down past me.” Ridgeway passed out again. When he woke up, it was dark and American artillery was pounding the area. Ruff said he had been hit again and begged Ridgeway not to leave him. Ridgeway said he wouldn’t. At some point that night, Ruff died. Ridgeway was awakened the following morning by someone pulling on his arm. He thought at first it was fellow Marines. But when he looked up, he realized it was a young North Vietnamese soldier trying to pull off his wristwatch. Agony and identification After the firefight, the shattered survivors of the patrol made it back to the combat base, and the dead were left on the battlefield. A rescue mission was deemed unwise by higher-ups, who feared losing even more men and depleting the base’s defenses, according to Pipes, who is now retired and lives in California. In a telephone interview, he said that with binoculars, he could see Marines’ bodies strewn on the battlefield. “It was worse than agony,” he said. No further patrols outside the combat base were immediately permitted. “We couldn’t go get them,” he said. “They laid out there for six weeks.” On March 17, he wrote to Ridgeway’s mother: “I am sorry that I can offer no tangible basis for hope concerning Ronald’s welfare.” Finally, on April 6, the Marines were able to return to the battlefield, Pipes said. What was left of the dead was brought back to Khe Sanh’s temporary morgue, where Pipes and others went about the grisly task of identifying the dead. “There wasn’t much there but bones and shoes and boots . . . [and] dog tags,” he said. In the end, of the 26 missing and presumed killed in action on Feb. 25, remains of all but nine were positively identified, according to Pipes and Stubbe. The unassociated body parts were sent home and placed in two caskets that would be buried beneath a large tombstone bearing the nine names of those unaccounted for, Stubbe said. The day of the funeral at the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery was sunny and cool. Ridgeway’s mother attended, and there were flags and solemn honors. A newspaper photographer took pictures. Far away, in North Vietnam, the rainy season was on, and Ridgeway was in his seventh month as a POW. The work of surviving As he sat alone in his windowless cell beside a wooden bed and the bucket he used for waste, Ridgeway went about creating a “make-believe” life. There was no one to talk to, and he was only allowed out once a day to empty the bucket. So he imagined that he was somewhere else, that he owned a pickup truck, that he had a wife and children, that he would go fishing. It was a mental exercise, he said, and he found that spending three days in his make-believe world would take up a whole day in solitary. Ridgeway said that by then, his captors considered him a “die-hard reactionary” and all Marines “animals.” He hadn’t cooperated with his guards. He had lied to interrogators, pretended he was green kid who had never fired his rifle and gave them bogus military information. The startled North Vietnamese soldier had locked and loaded his rifle when he realized Ridgeway was alive that morning. Ridgeway expected to be killed. “You didn’t hear about prisoners being taken,” he said. But he was bandaged, fed and marched away, through Laos and into North Vietnam. He spent time in several jungle camps, held in wooden leg stocks, and he eventually wound up in enemy prisons. He got lice, malaria and dysentery and lost 50 pounds. He wore pink-and-gray-striped POW pajamas and rubber sandals, all of which he brought home with him when he was freed. He was beaten with bamboo canes and tied up during interrogations. One interrogator the Americans named “Cheese” — because he seemed to be the big cheese — was especially cruel. He spoke English and sat up on a high chair as he questioned POWs tied on the floor. When he nodded his head, a guard would strike the prisoner with the bamboo cane. He had a face like a rat, Ridgeway recalled, and was a “mean . . . sadistical son of a b----.” Ridgeway said he didn’t dwell on the notion that people back home might think he was dead. They would be fine. His job was to survive. In January 1973, he was in North Vietnam’s notorious Hanoi Hilton prison when his captors abruptly announced that the POWs were to be freed as part of a peace agreement before the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam. When the list of POWs being released became public, Ridgeway’s name was on it.

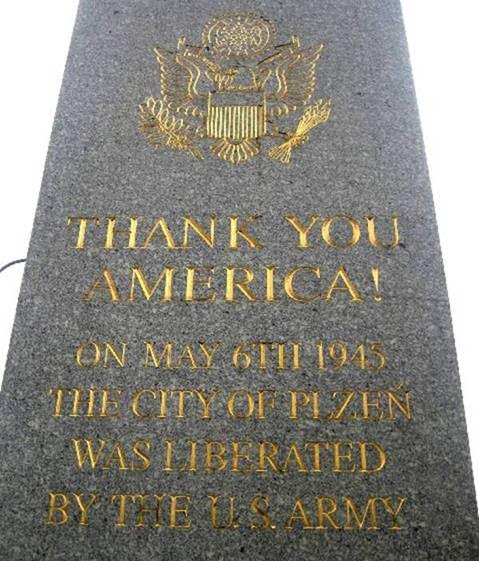

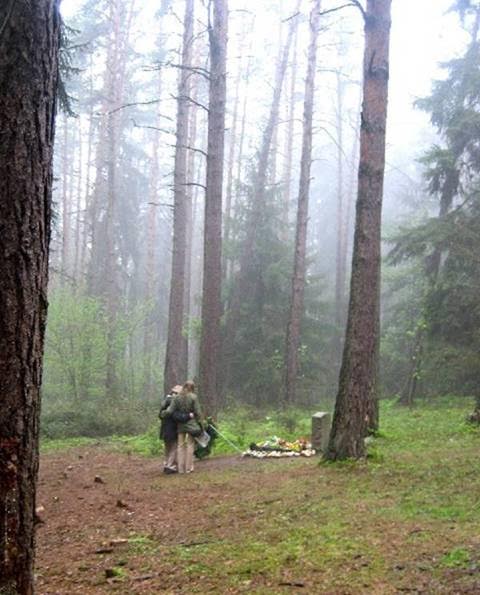

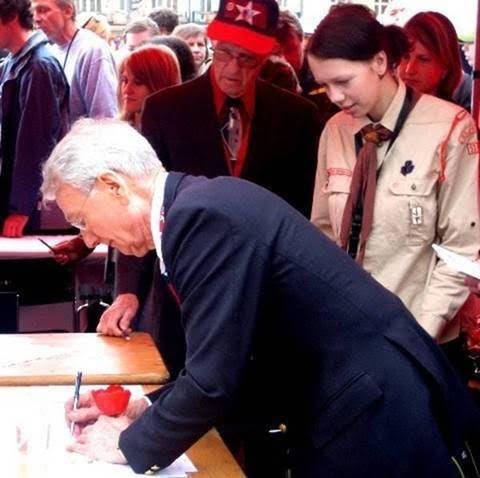

Back in Houston, his mother banged on a neighbor’s door and said, “Ronnie’s alive!” Memory etched in stone Ron Ridgeway was released on March 16, 1973. He came home, got married and went to college. “I came back in basically one piece,” he said. “I came back able to live my life. . . . We went over with a job to do. We did it to the best of our ability. We were lucky enough to come back. Several months after his return, he and his wife, Marie, went to Jefferson Barracks to see his tombstone, which was later replaced. “It brought back memories,” he said. “The loss of life of those that I knew. It was a solemn experience.” Carved in the surface were the words “Ambushed Patrol Died in Vietnam Feb. 25, 1968.” Eight names from the top: Ronald L. Ridgeway. Magda Jean-Louis contributed to this story. Mike is a general assignment reporter who also covers Washington institutions and historical topics. By Michael E. Ruane July 8 at 9:00 AM Submitted by Jim Kirk: This is an amazing story of remembrance. In the Czech Republic, the school children of the equivalent of fifth grade are each assigned one of the American and Canadian liberators buried there. Their grave is the student's responsibility for the year and they learn all there is to know of their own hero. Their surviving family is sent letters and they respond to the annual child who tends their loved one's grave. No apology needed here! Have you ever wondered if anyone in Europe remembers America 's sacrifice in World War II? There is an answer in a small town in the Czech Republic . The town is called Pilsen (Plzen). Every 5 years, Pilsen conducts the Liberation Celebration of the City of Pilsen in the Czech Republic. May 6th, 2010, marked the 65th anniversary of the liberation of Pilsen by General George Patton's 3rd Army. Pilsen is the town that every American should visit, because they love America and the American Soldier. Even 65 years later... by the thousands, The citizens of Pilsen came to say thank you. From the large crowds, to quiet reflective moments, to honor and remember their American hero. This is the crash site of Lt. Virgil P. Kirkham, the last recorded American USAAF pilot killed in Europe during WWII. It was Lt. Kirkham's 82nd mission and one that he volunteered to go on. At the time, this 20-year-old pilot's P-47 Thunderbolt plane was shot down, a young 14-year-old Czech girl, Zdenka Sladkova, was so moved by his sacrifice she made a vow to care for him and his memory. For 65 straight years, Zdenka, now 79-years-old, took on the responsibility to care for Virgil's crash site and memorial near her home. On May 4th, she was recognized by the Mayor of Zdenka's home town of Trhanova, Czech Republic, for her sacrifice and extraordinary effort to honor this American hero. Another chapter in this important story... the Czech people are teaching their children about America's sacrifice for their freedom. American soldiers, young and old, are the Rock Stars these children and their parents want autographs from. Yes, Rock Stars! As they patiently waited for his autograph, the respect this little Czech boy and his father have for our troops serving today was heartwarming and inspirational. The Brian LaViolette Foundation established The Scholarship of Honor in tribute to General George S. Patton and the American Soldier, past and present. Each year, a different military hero will be honored in tribute to General Patton's memory and their mission to liberate Europe. This award will be presented to a graduating senior who will be entering the military or a form of community service such as a fireman, policeman, teacher or nurse--a cause greater than self. The student will be from 1 of the 5 high schools in Pilsen, Czech Republic. The first award will be presented in May 2011 in honor of Lt Virgil Kirkham, that young 20-year-old P-47 pilot killed 65 years ago in the final days of WWII. Presenting Virgil's award was someone who knows the true meaning of service and sacrifice... someone who looks a lot like Virgil--Marion Kirkham, Virgil's brother, who himself served during WWII in the United States Army Air Corps!!! In closing, here is what the city of Pilsen thinks of General Patton's grandson. George Patton Waters (another Rock Star!), we're proud to say, serves on Brian's Foundation board. And it's front page news over there--not buried in the middle of the social section. Brigadier General Miroslav Zizka, 1st Deputy Chief of Staff, Ministry of Defense, Czech Armed Forces. Notice the flags? Share this with your family and friends ... every American should hear this story.

|

Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|