|

0 Comments

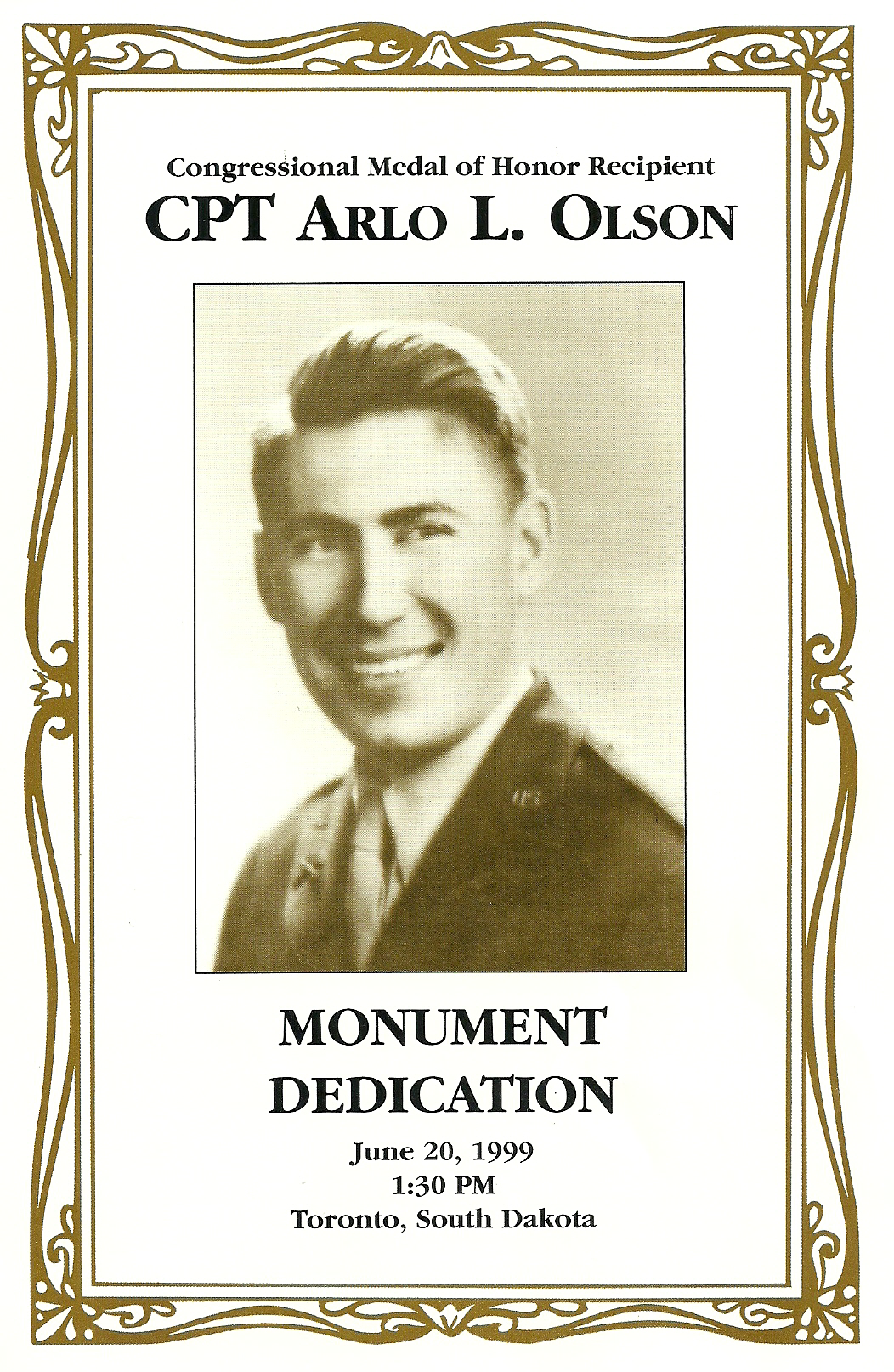

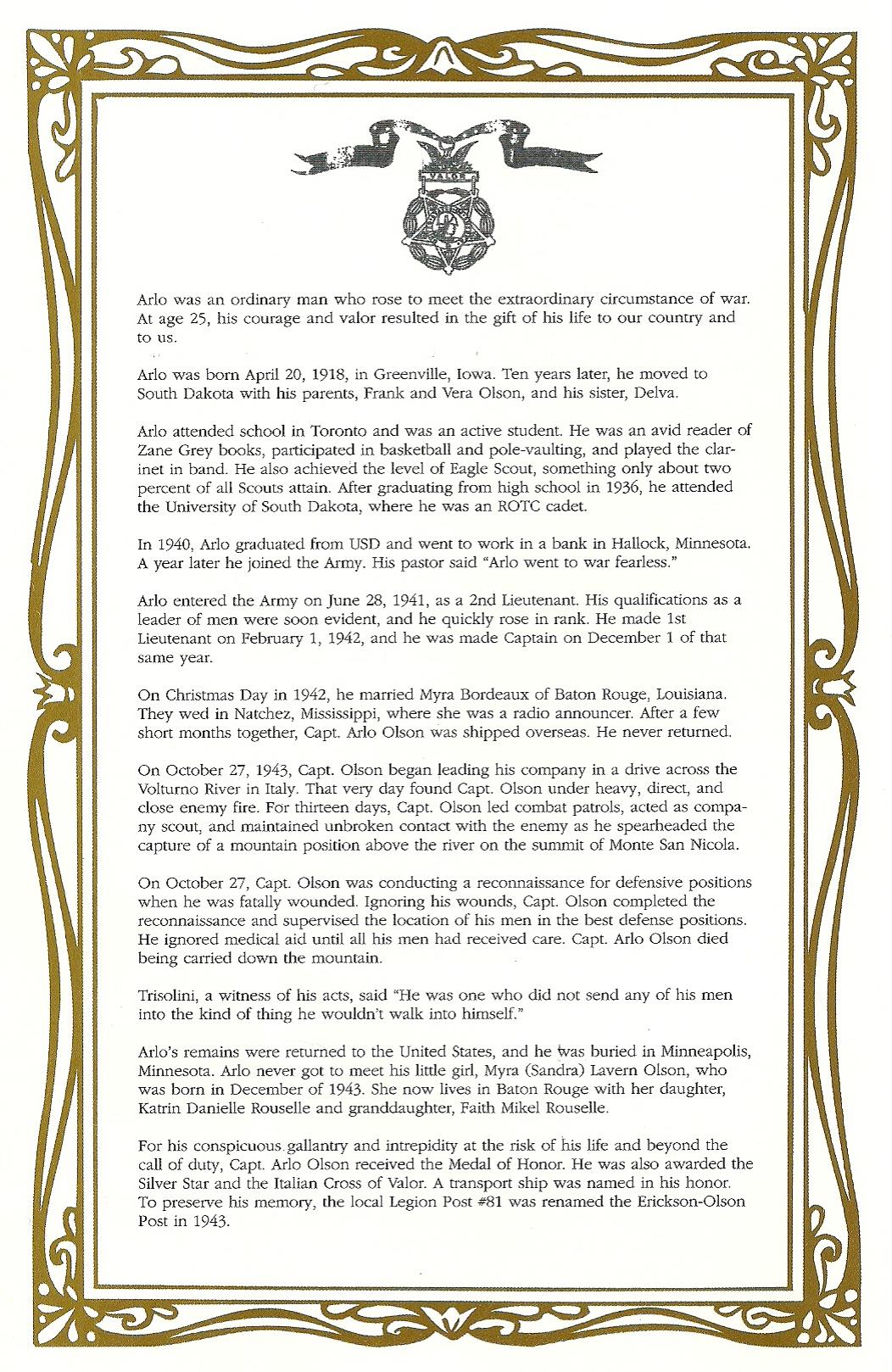

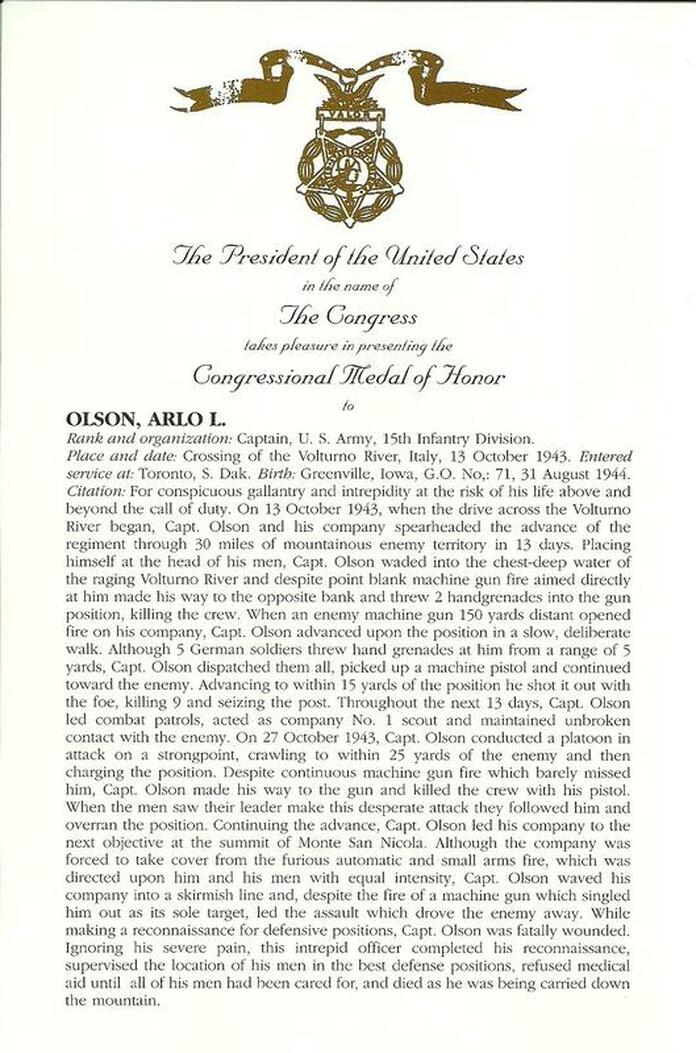

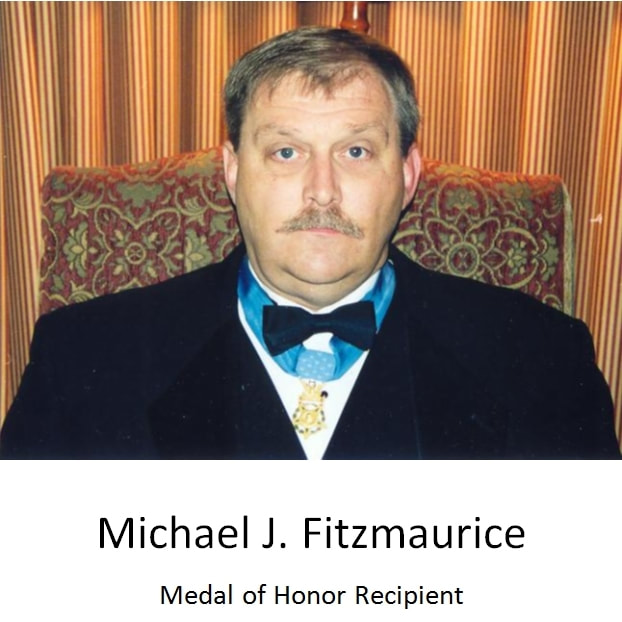

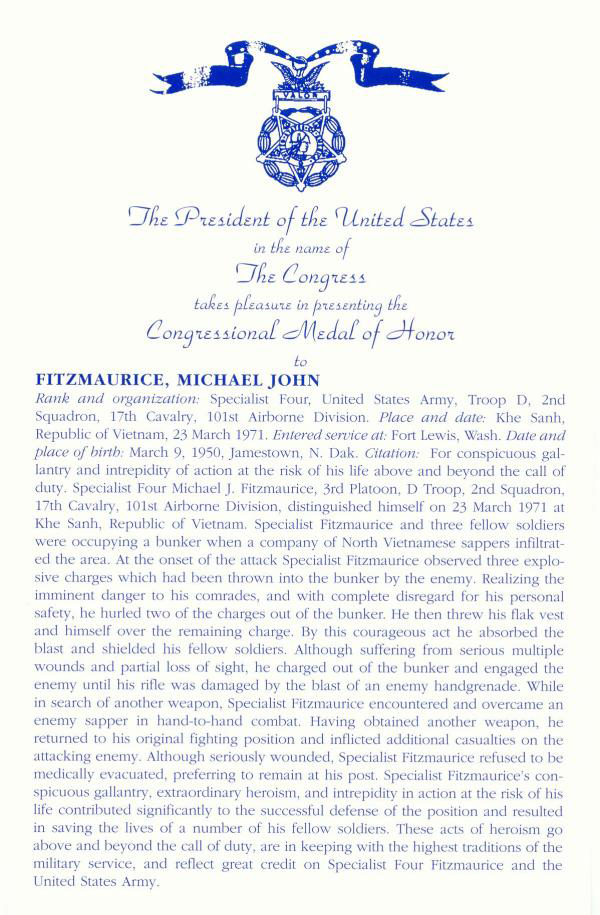

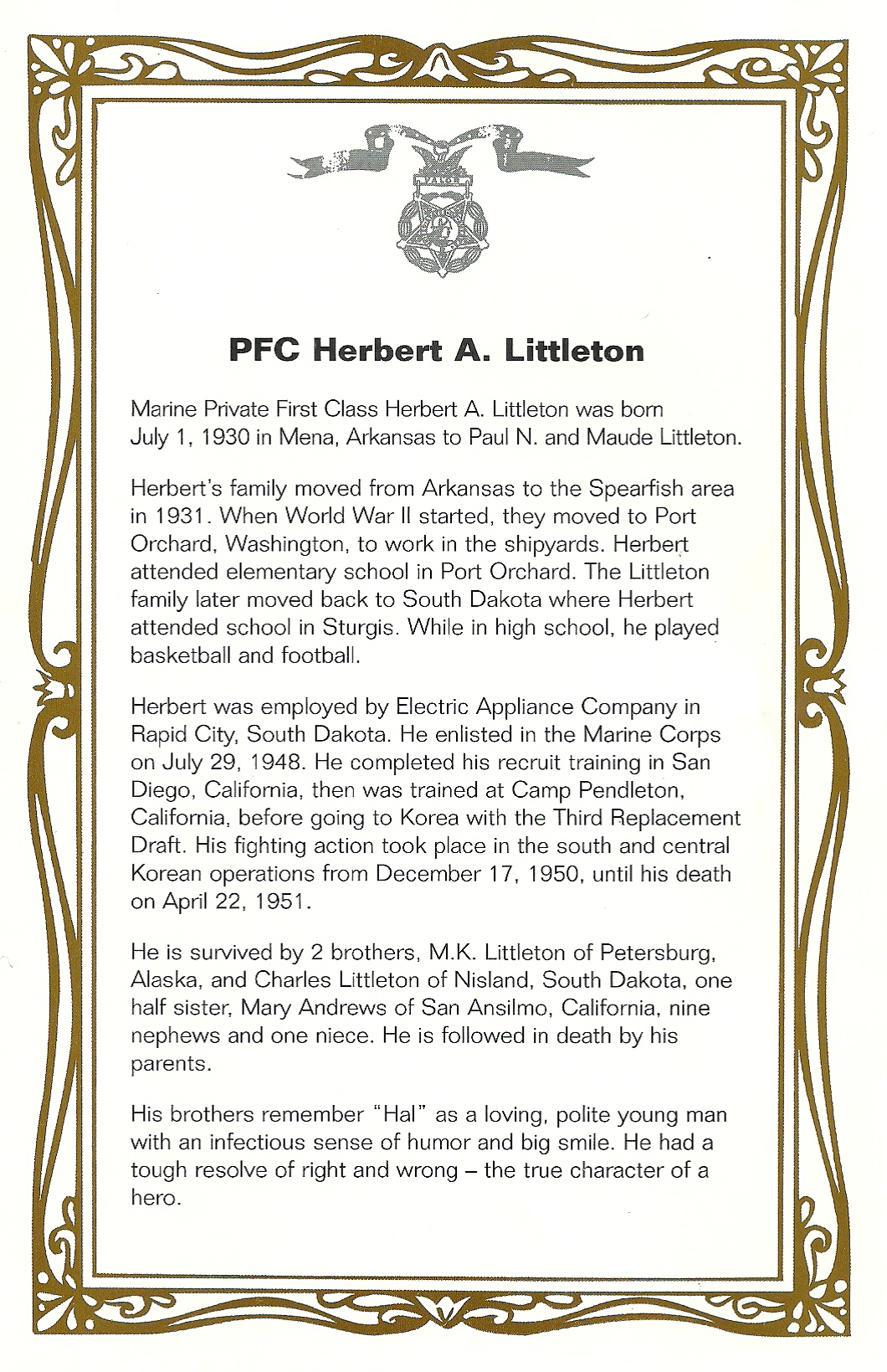

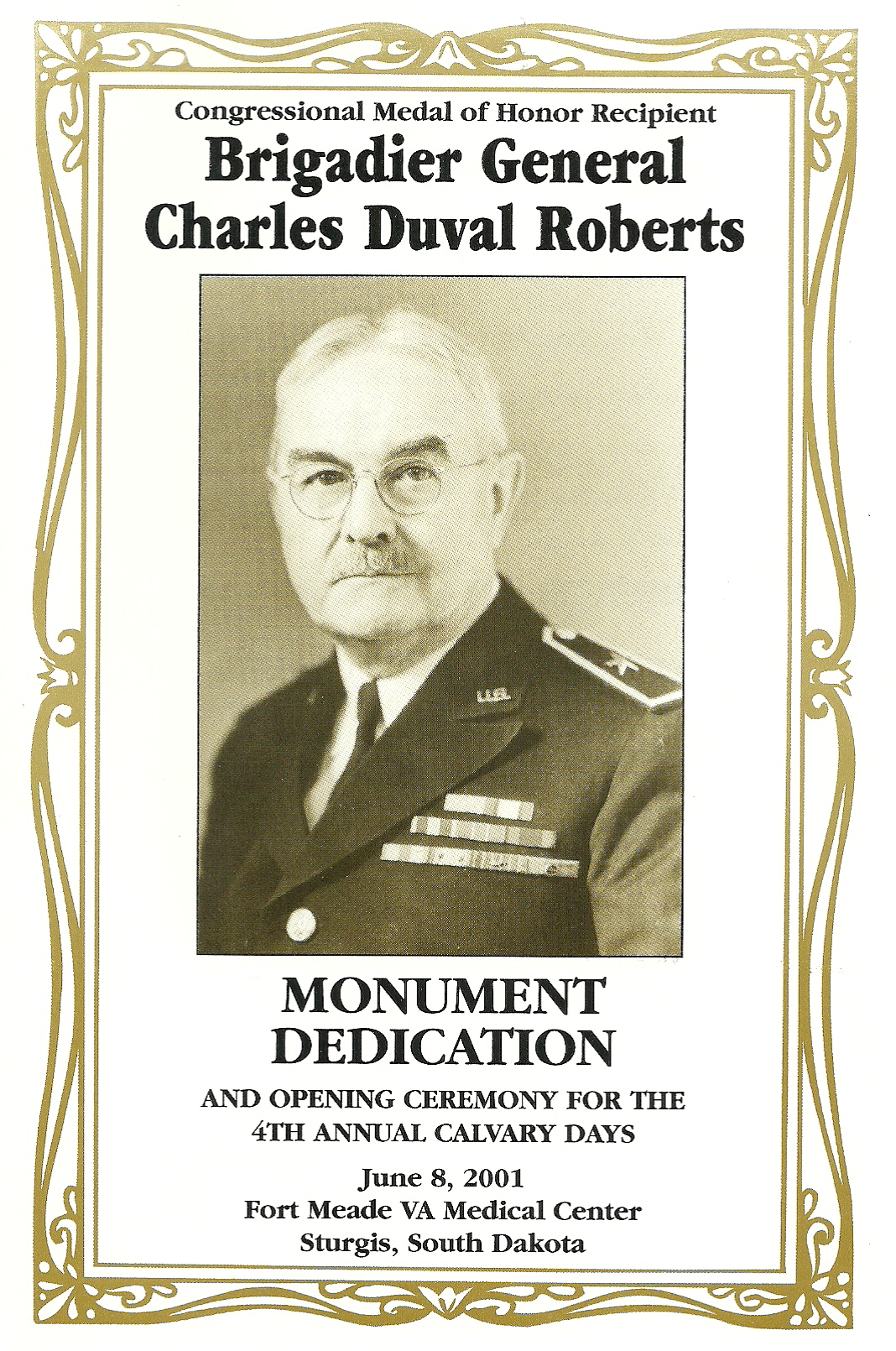

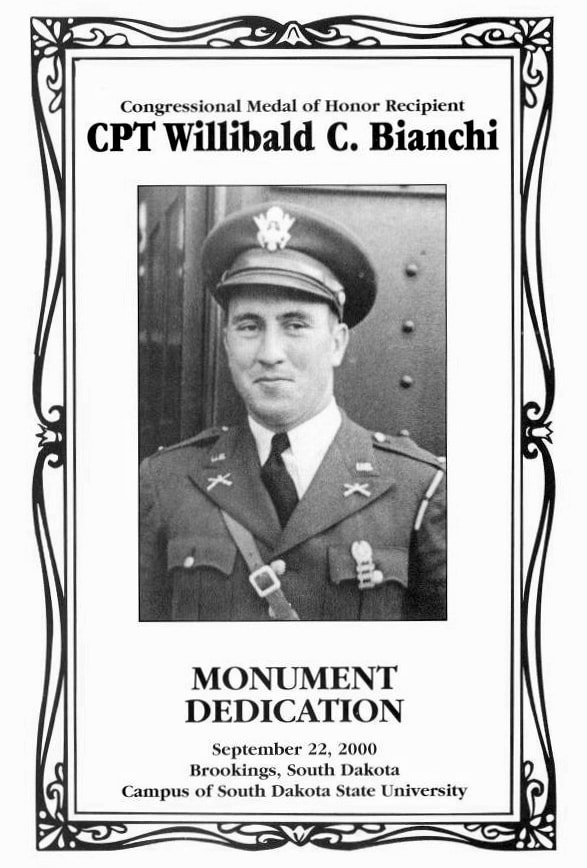

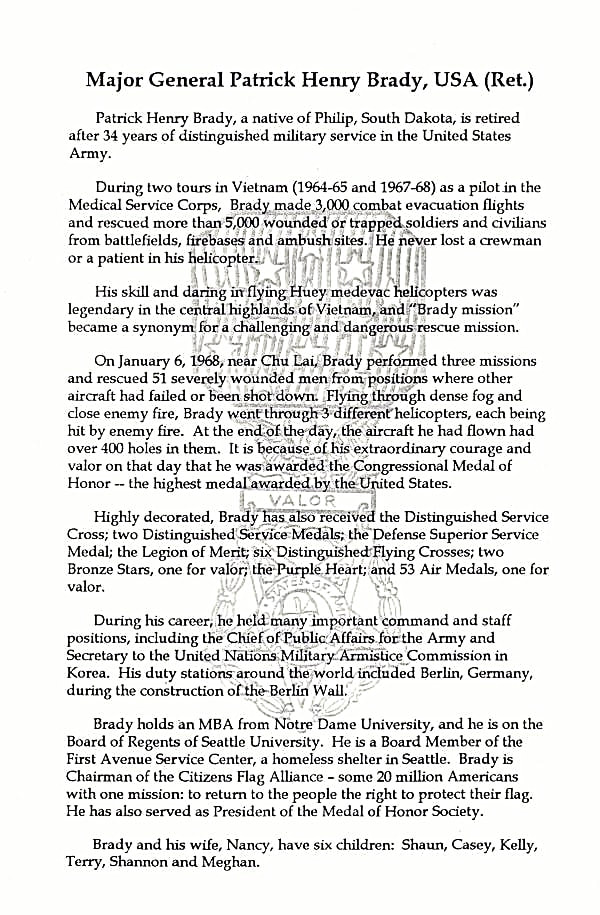

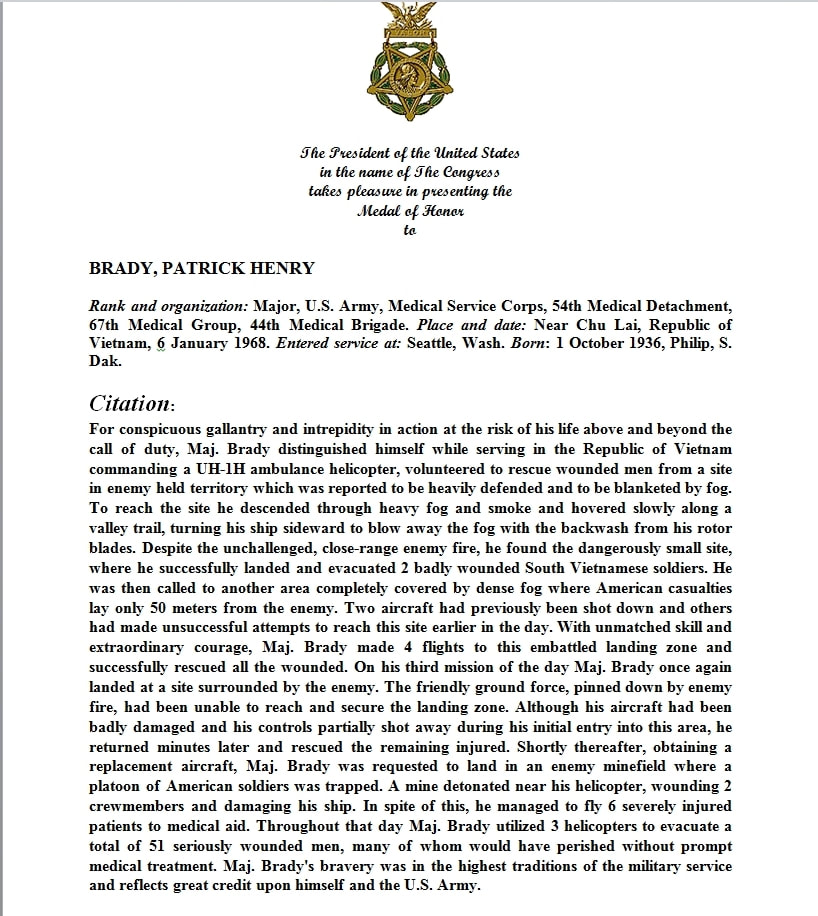

Submitted by Jim Hornstra from the South Dakota State Archives  JOSEPH JACOB FOSS Rank and Organization: Captain, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, Marine Fighting Squadron 121, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing Place and date: over Guadalcanal, 9 October to 19 November 1942, 15 and 23 January 1943 Entered Service at: South Dakota Born: 17 April 1915, Sioux Falls, S. Dak. Brigadier General Foss Died 1 January 2003 Citation: For outstanding heroism and courage above and beyond the call of duty as executive officer of Marine Fighting Squadron 121, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, at Guadalcanal. Engaging in almost daily combat with the enemy from 9 October to 19 November 1942, Capt. Foss personally shot down 23 Japanese planes and damaged others so severely that their destruction was extremely probable. In addition, during this period, he successfully led a large number of escort missions skillfully covering reconnaissance, bombing, and photographic planes as well as surface craft. On 15 January 1943, he added 3 more enemy planes to his already brilliant successes for a record of aerial combat achievement unsurpassed in this war. Boldly searching out an approaching enemy force on 25 January, Capt. Foss led his 8 F-4F Marine planes and 4 Army P-38 's into action and, undaunted by tremendously superior numbers, intercepted and struck with such force that 4 Japanese fighters were shot down and the bombers were turned back without releasing a single bomb. His remarkable flying skill, inspiring leadership, and indomitable fighting spirit were distinctive factors in the defense of strategic American positions on Guadalcanal. JOSEPH JACOB FOSS Joseph Jacob Foss, one of the United States’ outstanding aces of World War II and holder of the Nation’s highest military award, the Medal of Honor, was born 17 April 1915, on a farm near Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Following his graduation from high school in Sioux Falls, Joe Foss attended Augustana College for one year and Sioux Falls College for three semesters. He then enrolled at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion, and graduated in 1940 with a degree in Business Administration. In college, he fought on the boxing team and was a member of the track and football teams. The future Marine ace first became interested in flying when a squadron of Marine flyers staged an air show at Sioux Falls in 1932. Three years later, he had his first airplane ride, paying five dollars to go up with a barnstormer. In 1937, he paid $65 on the installment plan for his first course in flying. Now and then, he rented a Taylor craft. In 1939 he took a Civil Aeronautics Authority flying course at the University of South Dakota, and by the time, he graduated from college he had 100 hours of flying to his credit. While in college, he served in the South Dakota National Guard from October 1939 to March 1940. Three months later he hitchhiked to Minneapolis to enlist in the Marine Corps Reserve. Of the 28 men applying, only he and another were accepted on 14 June 1940 and assigned to inactive duty. Honorably discharged from the Reserve on 8 August 1940, he accepted an appointment as an aviation cadet in the Marine Corps Reserve the following day. He was called to active duty 23 August and sent to Pensacola, Florida, for training. He completed further training at Miami, received his Marine wings and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps Reserve on 31 March 1941. He was advanced to first lieutenant 10 April 1942, while serving as an instructor at Pensacola, and was promoted to captain 11 August1942 at Camp Kearney, California. Captain Foss arrived at Guadalcanal in September 1942 and became a Marine Corps ace on 29 October. Flying almost daily for one month he shot down 23 enemy planes during that period. Bagging three more later raised his total to 26, which tied the World War I record of the noted Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker and set a new record for World War II. His 26 planes included 20 Zero fighters, four bombers and two bi-planes. While at Guadalcanal, Capt. Foss was forced to make three dead-stick landings on Henderson Field as a result of enemy bullets crippling his engine. In November, he was shot down over the island of Malaita, after accounting for three Zeros himself. Not being a good swimmer, he had trouble getting ashore. He was picked out of the water by natives in a small boat and learned from them that, had he been able to swim, the direction in which he was headed would have carried him to a place on the beach that was infested with crocodiles. Captain Foss received the Distinguished Flying Cross from Adm. William F. Halsey for his heroism and extraordinary achievement in shooting down six Zeros and one bomber from 13 October to 30 October 1942. Returning to the United States in April 1943, he reported to Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., and was presented the Medal of Honor by President Franklin D. Roosevelt at ceremonies in the White House on 18 May 1943. Also in May of 1943, he was sent on a tour of Navy preflight schools and Naval Air Stations where Marines underwent training. After his 30-day rehabilitation leave, he went on a bond-selling tour of the United States and became engaged in a training assignment. He was promoted to major on 1 June 1943. Back in the Pacific in February 1944, Maj Foss was appointed squadron commander of Marine Fighting Squadron 115. He served in the combat zone around Emirau, St. Mathias Group, but failed to better his “shoot-down” record. Maj Foss returned to the United States in September 1944 and was ordered to Klamath Falls, Oregon. In February 1945, he became operations and training officer at the Marine Corps Air Station, Santa Barbara, California. With the end of the war in August 1945, he requested to be released to inactive duty. He went on terminal leave in October, but was ordered to Iowa that month to appear at Navy Day ceremonies in four cities there. Finally relieved from active duty on 8 December 1945, he was retained in the Marine Corps Reserve on inactive duty. Maj. Foss was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the South Dakota Air National Guard in September 1946. He tendered his resignation from the Marine Corps Reserve on 29 January 1947. It was accepted effective 19 September 1946, the day prior to his acceptance of the Air National Guard commission. On 20 September 1953, he was advanced to the rank of brigadier general in the South Dakota Air National Guard. In 1948, the future governor went into politics and won an election to South Dakota’s State House of Representatives. Two years later he made an unsuccessful bid in the Republican gubernatorial primary. He returned to the State Legislature and in June 1954, won an overwhelming victory for the gubernatorial nomination. He was elected Governor of South Dakota the following November, and was re-elected two years later. In 1960 he was named as the first commissioner of the American Football League and served in that position until 1966. From 1988 through 1990 he served as president of the National Rifle Association. Brigadier General Foss died 1 January 2003 at a hospital near his home in Scottsdale, Arizona, following a stroke. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. In addition to the Medal of Honor and Distinguished Flying Cross, his decorations and medals include: the Presidential Unit Citation, American-Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three bronze stars, and the World War II Victory Medal. The highest military medal awarded for bravery is the Medal of Honor. See other parts of this web site for a discussion of that medal and other medals for bravery awarded to Springfield veterans. I believe Springfield has one or two veterans with the second highest award for bravery and two or three with the third highest award. There have been nine South Dakotans awarded the Medal of Honor. They are Captain Willibald C. Bianchi, General Patrick H. Brady, Specialist Four Michael J. Fitzmaurice, Captain Joe J. Foss, Master Sergeant Woodrow W. Keeble, Private First Class Herbert A. Littleton, Captain Arlo L. Olson, Brigadier General Charles D. Roberts, Colonel Leo K. Thorsness. Thanks to Jim Hornstra we have write-ups on all nine and we will periodically publish one in our Sunday Feature section of this web site. Dick Martin Submitted by Jim Hornstra from the South Dakota archives Call it a difference of opinion, or a matter of interpretation. Call it whatever you wish, but the plain fact is that the United States Army and Michael J. Fitzmaurice do not seem to be of one mind when it comes to the events of March 23, 1971. For its part, the Army uses phrases like, “conspicuous gallantry,” and, “above and beyond the call of duty,” to describe what Fitzmaurice did when North Vietnamese soldiers attacked his unit’s position at Khesanh, Vietnam. They awarded him the Congressional Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest military decoration, for his actions. Fitzmaurice does not dispute the Army’s account of that night, but the self-effacing Hartford man does not seem convinced that his actions rose to the level of gallantry, either. He was just being a good soldier. Fighting as he had been trained, defending his post and helping the rest of his outfit live to see another day. He is quietly proud of that. As for earning the medal itself, there’s a very simple explanation for that. “I just got lucky,” he said. General William Westmoreland once compared the country of Vietnam to a don ganh — the pole that is carried across a man’s shoulders, with baskets suspended from either end — which has been used to carry burdens in Asia for thousands of years. Vietnam’s two most important regions, the Mekong River delta in the south and the Red River basin of the north, comprise the baskets; a slender strip of land hugging the South China Sea, the pole, connects these two. Near the center of that pole is the 17th Parallel, chosen as the dividing line between North and South Vietnam when the country was partitioned in 1954. Just south of that line, in the mountainous jungle near Laos, lies the village of Khesanh. Early in 1968, Khesanh was added to the roll of battle names that will resonate down through American military history when North Vietnamese troops attacked and surrounded the U.S. base there. What had been a relatively quiet, obscure outpost suddenly loomed large when it became the focal point of a 77-day siege that reduced the defending Marines’ existence to a hellish struggle for survival. A world away from Khesanh, in Iroquois, South Dakota, Michael Fitzmaurice was a junior in high school. By his own account, he did not pay much attention to the war back then. Following graduation in 1969 he and several classmates enlisted in the Army — he was the only one who ended up serving in Vietnam — and he left for boot camp on Halloween. By the following May, Fitzmaurice was in the war zone, assigned to the Second Squadron, 17th Cavalry, 101st Airborne Division. As a helicopter borne unit, the Second was a reactionary force: they were deployed to places where combat was already going on and another outfit needed help, or to help rescue the crews of downed aircraft who were under attack. At other times they were assigned to, “fly in and look things over,” as Fitzmaurice laconically described it, searching bunker complexes and other suspect areas. Fitzmaurice was in Vietnam for two months prior to the action at Khesanh. “I don’t know what a lot is,” said Fitzmaurice when asked how extensive his combat experience was during that time. “But we got shot at quite a few times. Nothing as serious as that night, though.” Fitzmaurice as a soldier Shortly after the battle of Khesanh in 1968, American forces had abandoned the base. When the decision was made to go into Laos three years later, however, the airstrip was again needed to support raids against the Ho Chi Minh trail, just across the border. Fitzmaurice’s unit was assigned to guard the airstrip. “We thought it was going to be good duty,” he said, grinning, but reality was quite different. “We were getting rocketed every night ... there were ground assaults.” On the night of March 23, the North Vietnamese attacked once again. A company-sized force broke through the perimeter to where the helicopters were parked, “and things kind of went downhill from there,” said Fitzmaurice. “I had just gotten off guard duty when they started coming in. I was wide awake,” he recalls. Fitzmaurice was in a bunker with three buddies when three hand grenades landed in their trench. “I threw two of them out, and covered the third with a flak jacket. It blew me up out of the hole, and that’s about it. I just stayed out there and finished up the fighting.” Fitzmaurice’s account is remarkable for its brevity, but the Army’s version of events is more illuminating. “Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice and three fellow soldiers were occupying a bunker when a company of North Vietnamese sappers infiltrated the area. At the onset of the attack Fitzmaurice observed three explosive charges which had been thrown into the bunker by the enemy. Realizing the imminent danger to his comrades, and with complete disregard for his personal safety, he hurled two of the charges out of the bunker. He then threw his flak vest and himself over the remaining charge. By this courageous act he absorbed the blast and shielded his fellow soldiers. “Although suffering from serious multiple wounds and partial loss of sight, he charged out of the bunker and engaged the enemy until his rifle was damaged by the blast of an enemy hand grenade. While in search of another weapon, Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice encountered and overcame an enemy sapper in hand-to-hand combat. Having obtained another weapon, he returned to his original fighting position and inflicted additional casualties on the attacking enemy. Although seriously wounded, Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice refused to be medically evacuated, preferring to remain at his post. Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice’s extraordinary heroism in action at the risk of his life contributed significantly to the successful defense of his position and resulted in saving the lives of a number of his fellow soldiers. These acts of heroism go above and beyond the call of duty, are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect great credit on Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice and the U.S. Army.” One of the three other soldiers in the bunker that night was Billy Fowler, from Georgia, Fitzmaurice’s closest friend in the whole outfit. “[Michael] was the first guy I met when I got over there,” Fowler remembered. “We just hit it off. But everybody liked him. He was just a good soldier.” The explosion that tossed Fitzmaurice out of the bunker partially buried another soldier and Fowler, “but all I got was one little piece of shrapnel in my back, never even had to go to the hospital,” he said. In the confusion of the firefight they lost contact, but he and the others were pretty sure what had happened to Fitzmaurice. “We all thought he was dead.” When the fighting ended that morning about sunrise, Fitzmaurice finally consented to be evacuated, and spent the next 14 months in and out of hospitals. He had numerous shrapnel wounds, one eye got dislocated, and the force of the explosion had raised havoc with his eardrums; doctors could not get the right side to heal properly for a long time. Fitzmaurice wears hearing aids in both ears today, which remarkably are his only ailments attributable to that night. Fitzmaurice does not know who initiated the Medal of Honor process. He was back in South Dakota, working at a packing plant in Huron, when he received notification. He was married by that time, so he and his wife, Patty, plus two brothers and his parents, were invited to the White House on October 15, 1973. There he received his medal from President Richard Nixon. “That was pretty interesting,” said Fitzmaurice. As the only Medal of Honor winner living in the state, Fitzmaurice is a somewhat reluctant celebrity. South Dakota Public Broadcasting did a segment on him for its Dakota Stories program, and he frequently gets requests for souvenirs or mementos from all over. He has been honored by the state twice. In 1996, 25 years to the day after the action at Khesanh, Gov. Bill Janklow presented Fitzmaurice with a special license plate, CMH1, in recognition of his accomplishment, and in October of 1998 the state Veterans Home in Hot Springs was renamed in his honor. Fitzmaurice works at the Royal C. Johnson Veterans Administration Hospital in Sioux Falls as a plumber these days. Seeing him walk the halls with a problem faucet in hand leads you to wonder: there were four men in the bunker the night those grenades landed. Michael Fitzmaurice acted, saving the others. Why him? Was it instinct? Exceptional courage? Something indefinable? Because of his genuinely humble nature, Michael Fitzmaurice is of little help in answering that question. “We were just trained to do what we had to do. We were all in this little hole. We weren’t going any place,” he said simply. If pressed, he will venture a little farther. “I was closest to [the charges]. I didn’t think about it. There are lots of things we wouldn’t do if we stopped to think about it.” Perhaps it is best for us all to leave his story there. Then we can believe that someday, if we find ourselves in a difficult situation, we might find within our hearts the capacity to be heroes, too. From, South Dakota Magazine The highest military medal awarded for bravery is the Medal of Honor. See other parts of this web site for a discussion of that medal and other medals for bravery awarded to Springfield veterans. I believe Springfield has one or two veterans with the second highest award for bravery and two or three with the third highest award. There have been nine South Dakotans awarded the Medal of Honor. They are Captain Willibald C. Bianchi, General Patrick H. Brady, Specialist Four Michael J. Fitzmaurice, Captain Joe J. Foss, Master Sergeant Woodrow W. Keeble, Private First Class Herbert A. Littleton, Captain Arlo L. Olson, Brigadier General Charles D. Roberts, Colonel Leo K. Thorsness. Thanks to Jim Hornstra we have write-ups on all nine and we will periodically publish one in our Sunday Feature section of this web site. Dick Martin Submitted by Jim Hornstra from the South Dakota archives  Submitted by Jim Hornstra from the South Dakota Archives  MASTER SERGEANT WOODROW WILSON KEEBLE Woodrow Wilson Keeble was born in Waubay, South Dakota, to Isaac and Nancy (Shaker) Keeble on May 16, 1917. While still very young, he moved to Wahpeton, North Dakota, where his mother worked at the Wahpeton Indian School (now called Circle of Nations School). Woodrow excelled in athletics, especially baseball, and pitched the Wahpeton amateur team to ten straight victories. He was being recruited by the Chicago White Sox when his Army National Guard unit was called up to serve in World War II. In World War II, Keeble served with I Company of the famed North Dakota 164th Infantry Regiment. After initial training in Louisiana, the regiment deployed to Australia in preparation for operations in the Pacific Theater. Keeble's unit was assigned to the Americal Division (officially the 23th Infantry Division). The 164th landed on Guadalcanal on October 13, 1942, to help the battered First Marine Division clear the South Pacific island of Japanese. Keeble's regiment of Dakotans was the first United States Army unit to conduct an offensive operation against the enemy in any theater. During these battles, Keeble's reputation for bravery and skill grew. Nearly a head taller than most of his fellow soldiers, he was an expert with the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). His other great weapon was his pitching arm, which he used to hurl hand grenades with deadly accuracy. James Fenelon, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota who fought with Keeble on Guadalcanal, once remarked that “The safest place to be was right next to Woody.” After the battles on Guadalcanal, Keeble and the rest of the regiment participated in combat campaigns on the islands of Bougainville, Leyte, Cebu, and Mindanao. Following the Japanese surrender, the entire Americal Division landed in Japan and took part in the occupation of the Yokohama region. After the war, Keeble returned to Wahpeton and worked at the Wahpeton Indian School. In 1947, Woodrow Wilson Keeble married Nettie Abigail Owen-Robertson. The 164th Infantry Regiment was reactivated in 1951 during the Korean War; they trained at Camp Rucker, Alabama. When Keeble's commanding officer had to select several sergeants for deployment to the front lines, he decided to have his men draw straws. Keeble volunteered instead. Asked why, Keeble said, “Somebody has to teach these kids how to fight.” Keeble, described as a gentle giant by his friends, was a ferocious warrior in battle, as evidenced by his heroic actions during Operation Nomad-Polar. Official records confirm Keeble was initially wounded on October 15, and then again on October 17, 18, and 20 - for which he received only one Purple Heart. For his bravery on the 18th, he was awarded a Silver Star. His heroism on the 20th made Keeble a legend - and 57 years later resulted in his posthumous Medal of Honor. His bravery in the face of enemy fire was so remarkable that a recommendation that he receive the Medal of Honor was twice submitted. In both cases, the recommendation was lost. When Keeble's men endeavored to submit the recommendation a third time, officials informed them they were too late; the 24th Division had reached its quota of Medal of Honor recipients. After reconsideration, Keeble was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by President George W. Bush, and was the first Sioux Indian to receive this award. Woodrow W. Keeble died January 28, 1982, and is buried at Sisseton, South Dakota. The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, March 3, 2008, has awarded in the name of Congress the Medal of Honor to MASTER SERGEANT WOODROW W. KEEBLE UNITED STATES ARMY Citation The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor to Master Sergeant Woodrow W. Keeble, United States Army, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity, at the risk of his life, above and beyond the call of duty: In action with an armed enemy near Sangsan-ni, Korea, on 20 October, 1951. On that day, Master Sergeant Keeble was an acting platoon leader for the support platoon in Company G, 19th Infantry, in the attack on Hill 765, a steep and rugged position that was well defended by the enemy. Leading the support platoon, Master Sergeant Keeble saw that the attacking elements had become pinned down on the slope by heavy enemy fire from three well-fortified and strategically placed enemy positions. With complete disregard for his personal safety, Master Sergeant Keeble dashed forward and joined the pinned-down platoon. Then, hugging the ground, Master Sergeant Keeble crawled forward alone until he was in close proximity to one of the hostile machine-gun emplacements. Ignoring the heavy fire that the crew trained on him, Master Sergeant Keeble activated a grenade and threw it with great accuracy, successfully destroying the position. Continuing his one-man assault, he moved to the second enemy position and destroyed it with another grenade. Despite the fact that the enemy troops were now directing their firepower against him and unleashing a shower of grenades in a frantic attempt to stop his advance, he moved forward against the third hostile emplacement, and skillfully neutralized the remaining enemy position. As his comrades moved forward to join him, Master Sergeant Keeble continued to direct accurate fire against nearby trenches, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy. Inspired by his courage, Company G successfully moved forward and seized its important objective. The extraordinary courage, selfless service, and devotion to duty displayed that day by Master Sergeant Keeble was an inspiration to all around him and reflected great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army. The highest military medal awarded for bravery is the Medal of Honor. See other parts of this web site for a discussion of that medal and other medals for bravery awarded to Springfield veterans. I believe Springfield has one or two veterans with the second highest award for bravery and two or three with the third highest award. There have been nine South Dakotans awarded the Medal of Honor. They are Captain Willibald C. Bianchi, General Patrick H. Brady, Specialist Four Michael J. Fitzmaurice, Captain Joe J. Foss, Master Sergeant Woodrow W. Keeble, Private First Class Herbert A. Littleton, Captain Arlo L. Olson, Brigadier General Charles D. Roberts, Colonel Leo K. Thorsness. Thanks to Jim Hornstra we have write-ups on all nine and we will periodically publish one in our Sunday Feature section of this web site. Dick Martin Col Leo K ThorsnessSubmitted by Jim Hornstra

|

Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|