Submitted by Daryl Heusinkveld Seventy-five years ago, this month, a Band of Roughnecks went abroad on a top-secret mission into Robin Hood's stomping grounds to punch oil wells to help fuel England's war machines. It's a story that should make any oilman or woman proud. The year was 1943 and England was mired in World War II. U-boats attacked supply vessels, choking off badly needed supplies to the island nation. But oil was the commodity they needed the most as they warred with Germany. A book "The Secret of Sherwood Forest: Oil Production in England During World War II" written by Guy Woodward and Grace Steele Woodward was published in 1973 and tells the obscure story of the American oil men who went to England to bore wells in a top-secret mission in March 1943. England had but one oil field, in Sherwood Forest of all places. Its meager output of 300 barrels a day was literally a drop in the bucket of their requirement of 150,000 barrels a day to fuel their war machines. Then, a top-secret plan was devised: to send some Americans and their expertise to assist in developing the field. Oklahoma based Noble Drilling Co., along with Fain-Porter signed a one-year contract to drill 100 wells for England, merely for costs and expenses. Forty-Two drillers and roughnecks from Texas and Oklahoma, most in their teens and early twenties, volunteered for the mission to go abroad. The hands embarked for England in March 1943 aboard the HMS Queen Elizabeth. Four National 50 drilling rigs were loaded onto ships, but only three of them made landfall; the Nazi U-boats sank one of the rigs en route to the UK. The Brits' jaws dropped as the Yanks began punching the wells in a week, compared to five to eight weeks for their British counterparts. They worked 12-hour tours, 7 days a week and within a year, the Americans had drilled 106 wells and England oil production shot up from 300 barrels a day to over 300,000. The contract fulfilled, the American oil men departed England in late March 1944, but only 41 hands were on board the return voyage. Herman Douthit, a Texan derrick-hand was killed during the operation. He was laid to rest with full military honors and remains the only civilian to be buried at The American Military Cemetery in Cambridge. "The Oil Patch Warrior," a seven-foot bronze statue of a roughneck holding a four-foot pipe wrench, stands near Nottingham, England to honor the American oil men's assistance and sacrifice in the war. A replica was placed in Ardmore, Oklahoma in 2001. Special thanks to the American Oil and Gas Historical Society.

0 Comments

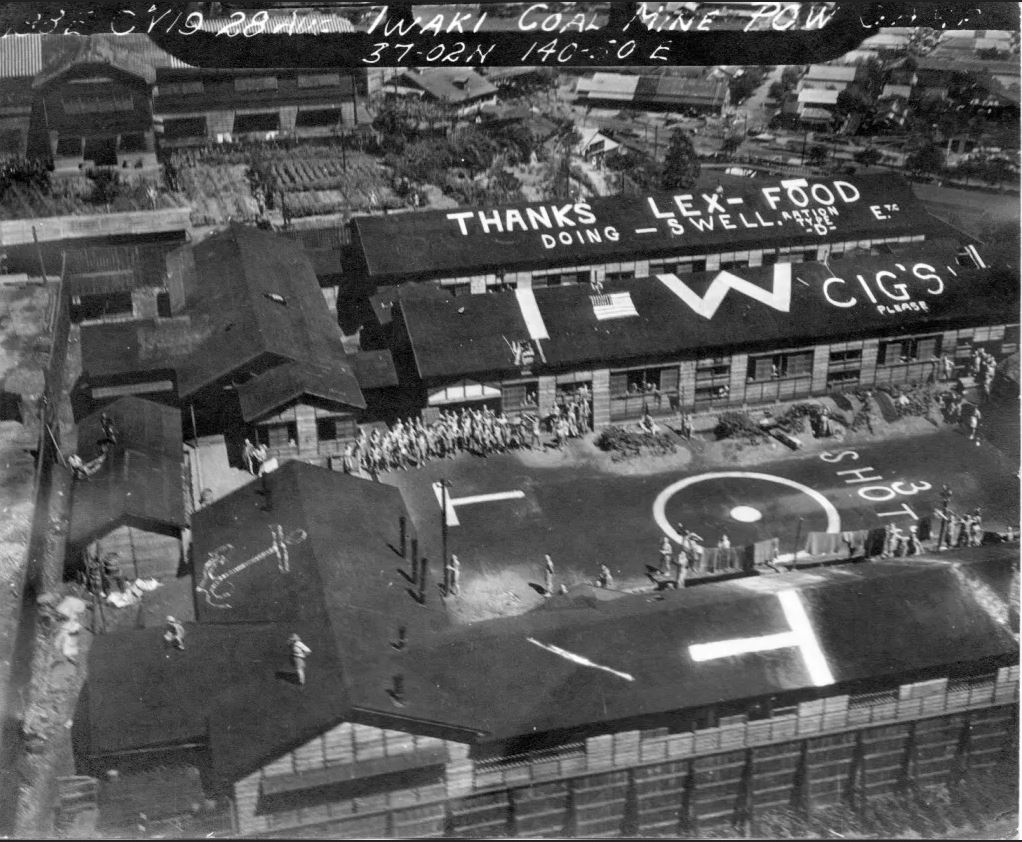

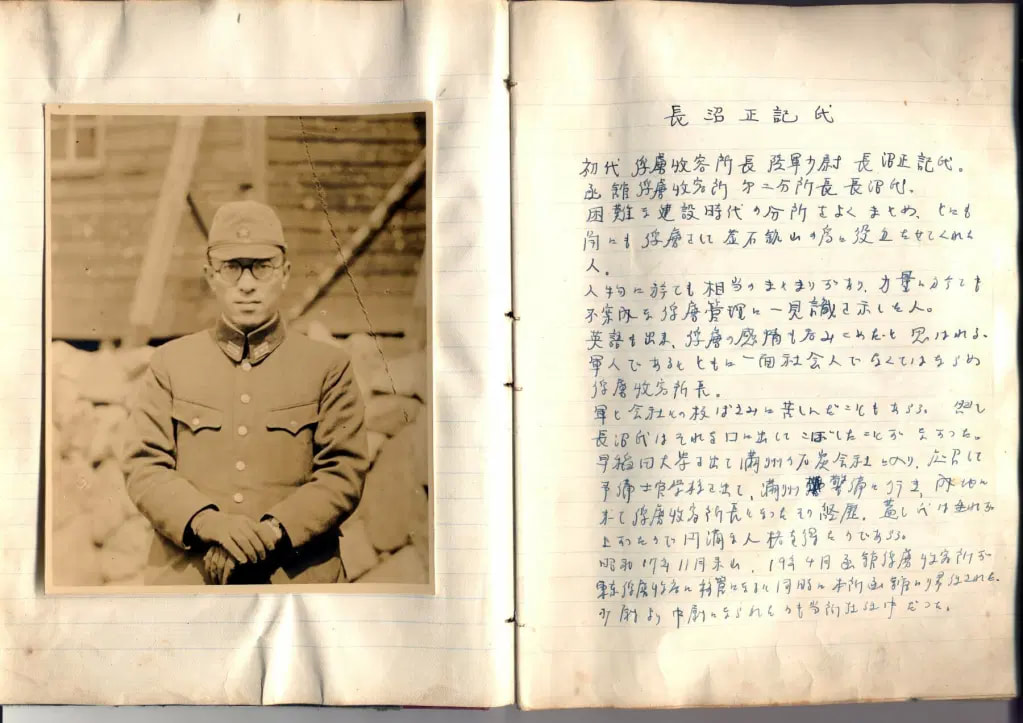

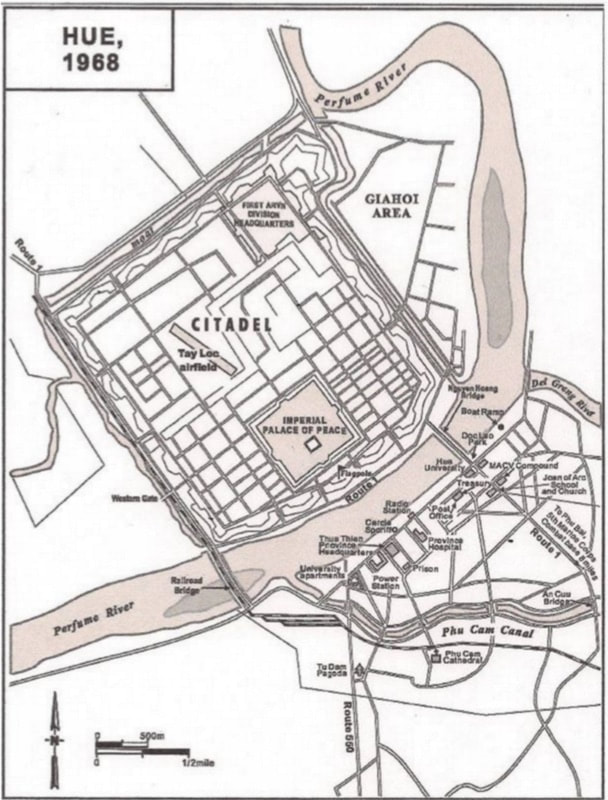

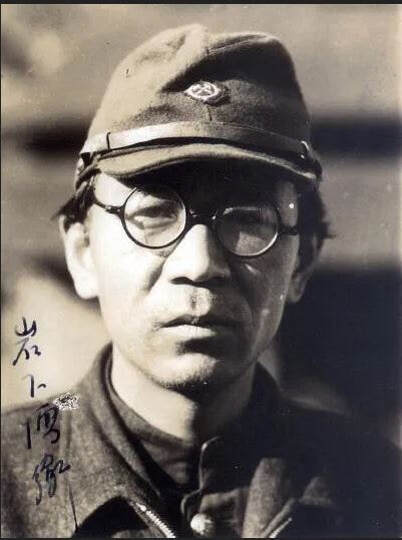

Hue was the capital of Thua Thien Province and South Vietnam’s third largest city. It was the old imperial capital and served as the cultural and intellectual center of Vietnam. Hue City was really two cities divided by the Perfume River. The Old City (Citadel) was North of the Perfume River, and the New City was South of the Perfume River. The Citadel on the North side of the Perfume River (See Map) covered three square miles, was protected by an outer wall thirty (30) feet high and ninety (90) feet thick and was in the form of a square tilted on a vertex when viewed from a North-South perspective. It had northeastern, southeastern, southwestern and northwestern walls. (See map) The sides of the square were 3000 yards (approximately 1 3/4ths miles) on each side, and surrounded by a moat ninety (90) feet wide and twelve (12) feet deep. The Citadel consisted of block after block off houses, parks, villas and the Imperial Palace. Hue had been remained remarkably free of the war until the TET holiday which began on January 31, 1968. The TET Offense was countrywide and was put down in a week except at Hue City where the North Vietnam Army (NVA) decided to make a stand. Dan Mejstrik, a veteran from Springfield, was a hospital corpsman (medic) with third platoon of D Company of the First Battalion, Fifth Marine Regiment and was caught in the middle of the battle for Hue City during the Tet Offensive. The battle was one of the fiercest of the Vietnam War with half the Marines entering the fray being killed or wounded. The following is a summary of the actions of Dan’s battalion until Dan was wounded and taken out of the battle. I have put Dan’s name in parenthesis (Dan) so he could be followed through the battle. Feb 11 – Helicopters take two platoons of Co B, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, from Phu Bai, the Marine headquarters eight miles south of Hue City on Route One, direct to Mang Ca compound which was in the Northeast part of the Citadel. The rest of the battalion trucks to the MACV compound on the south side of the Perfume River in Hue City. Feb 11 – Enemy totals 8,000 soldiers and holds half of Northeast wall and all of Southeast wall of the Citadel. Feb 11 – Weather turns nasty in afternoon. Feb 12 – Company A and Company B’s third platoon leave from MACV Compound on the South side of the Perfume River across the river along the moat and into the Citadel through a breach (gate) in the Northeastern wall. Feb 13 – Company A,B, and C leave Mac V Compound on the South side of the Perfume River and in Navy landing craft arrive at Mang Ca Compound (1st ARVN Division HQ) in the Northeast part of the Citadel. Feb 13 – A Company leads the way against the enemy and immediately takes 35 casualties and is rendered ineffective. Feb 13 – A Co falls back and B and C Company move forward 300 meters but are stopped by intense enemy fire coming from the Dong Ba Tower at the Dong Ba Gate. Feb 14 –First Battalion Commander requests rules of engagement changed to allow bombing and artillery. Request granted. Artillery, Naval and Air called in to soften up the enemy by hitting the Tower. Feb 14 – Late in the day, Company D (Dan) boards Navy landing craft at MACV HQ and crosses the Perfume River to get to the Citadel. Dan Mejstrik: “I have been asked that knowing what hell I was heading into, was there any reluctance to board the landing craft and my answer was that I was scared but everyone else was going so I went too.” Feb 15 – In the morning, Company D (Dan) is sent against the Dong Ba Tower. Feb 15 - Artillery, Naval and Air bombardment collapse and reduce the tower to rubble, making it more difficult to eliminate the enemy from the key terrain (tower) that was so important for them to hold. Feb 15 – Dan’s third platoon gains a toehold at Dong Ba Tower. Feb 15 - Rest of Company D is committed and overruns the Tower. Dan Mejstrik: “The Dong Ba Tower was the focal point of my company (D). The enemy was intent on holding the tower because they could bring fire on our battalion and any of the other American or South Vietnamese units in the Citadel. My platoon gained a toehold at the tower. The rest of D Company joined us and we did a frontal assault on the tower, the way Marines like to do things. The assault consisted of D Company attacking the tower with small arms and grenades and then falling back as the entrenched enemy opened up with their small arms and grenades. We would then attack again with small arms and grenades and then fall back under the enemy’s small arms and grenades. It was kind of a grenade battle. This went on until we finally overran the enemy resistance. The medic’s job was to join in the assaults and haul the dead and wounded back to our position.” Feb 16 – Under fire from three directions, First Battalion (Dan) continues assault on Southeastern wall. Dan Mejstrik: “What may surprise some is that after being under fire for so long, one of the many emotions you feel is anger. You get angry and want to kill the Enemy that is putting you through such hell.” Feb 17 – All of 1st Battalion (Dan) continues its lethal assault on the Southeastern wall of the Citadel. At this point, the First Battalion, under constant fire, had already suffered 47 killed and 240 wounded in just five days inside the Citadel. Feb 18 – First Battalion (Dan) takes a break in preparation for renewing the assault on the Southeastern wall the next morning. Dan Mejstrik: “Part of the exhaustion is the adrenalin high you are on for such a long time.” Feb 19 – After intense bitter fighting, the First Battalion (Dan) gets near the wall. Feb 20 – The weather clears. Dan Mejstrik: “Could have fooled me! My senses were focused totally on the danger all around me. I had no sense of what the weather was.” Feb 20 – First Battalion (Dan), exhausted, takes a break. Feb 20 – In the afternoon, the officers of the battalion gather to decide the next move. Feb 20 – Despite the reluctance of the company commanders, a night attack is planned with A company taking the lead. Feb 21 – At 0300 hours, second platoon of A company moves out. They initially meet no resistance, but come across a number of unsuspecting NVA soldiers that they eliminate. The rest of the battalion (Dan) follows and in intense fighting comes within a hundred yards of the Southeastern wall. Feb 21 – The battalion experiences random sniper and mortar fire as they approach the Southeastern wall. One of the random mortar rounds lands right in the middle of hospital corpsman (medic) Dan Mejstrik and six or seven other Marines. Dan immediately begins to attend to the wounded Marines when he notices that blood was appearing, out of nowhere, on the Marine he is working on. He finally realizes he has been hit by shrapnel from the mortar round and he is seriously wounded. He instructs some of the Marines in patching him up and is medevaced out. He loses an eye and has other shrapnel injuries. The war was over for Dan Mejstrik. He spends a number of months in rehabilitation and returns home. Dan Mejstrik: “Evacuating the wounded was a real problem. In some cases, their liters were put on tanks for a bumpy ride out of the combat zone. One bit of luck for me was that I was evacuated on a helicopter full of colonels that just happened to be leaving at that time.” The battle for Hue City rages on for a few more days. The Imperial Palace is taken and the rest of the city is cleared out of enemy soldiers. The city has been destroyed. DICK MARTIN written by George MacDonald Featured image: Survivors from the Battle of Hong Kong who were held at Ohashi Prison Camp, photographed prior to their evacuation on September 15th, 1945. The author, then age 23, appears in the back row, fourth from the left. It was noon on August 15th, 1945. The Japanese Emperor had just announced to his people that his country had surrendered unconditionally to the Allied Powers. To those of us being held at Ohashi Prison Camp in the mountains of northern Japan, where we’d been prisoners of war performing forced labor at a local iron mine, this meant freedom. But freedom didn’t necessarily equate to safety. The camp’s 395 POWs, about half of them Canadians, were still under the effective control of Japanese troops. And so we began negotiating with them about what would happen next. Complicating the negotiations was the Japanese military code of Bushido, which required an officer to die fighting or commit suicide (seppuku) rather than accept defeat. We also knew that the camp commander—First Lieutenant Yoshida Zenkichi—had written orders to kill his prisoners “by any means at his disposal” if their rescue seemed imminent. We also knew that we could all easily be deposited in a local mine shaft and then buried under thousands of tons of rock for all eternity without a trace. We had no way of notifying Allied military commanders (who still hadn’t landed in Japan) as to the location of the camp (about a hundred miles north of Sendai, in a mountainous area near Honshu’s eastern coast), whose existence was then unknown. Because of the devastating American bombing, Japan’s cities had been reduced to rubble, its institutions were in chaos, and millions of Japanese were themselves close to starvation, much like us. The camp itself had food supplies, such as they were, for just three days. Lieut. Zenkichi seemed angry, and felt humiliated by the surrender. Yet he appeared willing to negotiate our status. And after some stressful hours, we reached an agreement: The Japanese guards would be dismissed from the camp, while a detachment of Kenpeitai (the much feared Military Police) would provide security for Zenkichi, who would confine himself to his office. The author, who appears in the featured image, fourth from left in the top row To our delight, the local Japanese farmers were friendly, and agreed to give us food in exchange for some of the items we’d managed to loot from the camp’s remaining inventory—though, unfortunately, not enough to feed the camp. Meanwhile, through a secret radio we’d been operating, we learned that the Americans were going to conduct an aerial grid search of Japan’s islands for prison camps. We followed the broadcasted instructions and immediately painted “P.O.W.” in eight-foot-high white letters on the roof of the biggest hut. Two days later, with all of our food gone, we heard a murmur from the direction of the ocean. The sound turned into the throb of a single-engine airplane flying at about 3,000 feet altitude. Then, suddenly he was above us—a little blue fighter with the white stars of the US Navy painted on its wings and fuselage. But the engine noise began to fade as he went right past us. Please, God, I thought—let him see our camp. Then the engine sound grew stronger, and changed its pitch as we heard the roar of a dive. The pilot had wrapped around a nearby mountain and came straight down the center of the valley, his engine now bellowing wide open. From just over treetop altitude, he flew over the center of the camp. We all went wild: Our prayers had been answered. 1945 American aerial photo of Ohashi prison camp Then he climbed to about 7,000 feet while circling above us—we assumed he was radioing our location to base—before making another pass over the camp, as slowly as he dared, this time with his canopy back. He threw out a silver tin box on a long streamer that landed in the center of the camp. Inside, we found strips of fluorescent cloth and a hand-written note: “Lieutenant Claude Newton (Junior Grade), USS Carrier John Hancock. Reported location.” The instructions for the cloth strips were as follows: “If you want Medicine, put out M. If you want Food, put out F. If you want Support, put out S.” We put out “F” and “M.” Once more, Lieut. Newton flew over the camp, this time to read the letters we’d written on the ground. Waggling his wings, he headed straight out to sea to his floating home, the John Hancock. Seven hours later, two dozen airplanes approached the camp from the sea. They were painted with the same US Navy colors, but these were much larger planes—Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers with a crew of two. Each made two parachute cargo drops in the center of camp, leaving us with a ton or more of food and medicine. The boxes contained everything from powdered eggs to tins of pork and beans. There was also something called “Penicillin” that, I later learned, doctors had begun prescribing to infected patients in 1942. (Our camp doctor had understandably never heard of it.) That night, we had a feast and a party. Despite the doctor’s warnings not to overdo it, we did. The sudden calorie intake nearly killed us. August 28, 1945 photo in the collection of Peter Somerville, son of a naval aviator operating on the USS Hancock But it was one thing for the Americans to drop supplies, and another thing to get to us. The days passed, until one sunny morning we had another aerial visitor from the east. He circled the camp and dropped a note: “Goodbye from Hancock and good luck. Big Friends Come Tomorrow.” The “friends” arrived at about 10am the next day, and they were indeed big: four-engine B-29 Superfortresses. Like the Penicillin, this was something new: These planes hadn’t entered service till 1944, and none of us had seen one. Their giant bomb-bay doors opened and out came wooden platforms, each loaded with parachute-equipped 60-gallon drums. These were packed with tinned rations and other supplies, including new uniforms and footwear. None of this was lost on nearby Japanese villagers, who saw us POWs going from starvation to a state of plenty. Since our newfound wealth was scattered all over hell’s half acre, we asked these locals to bring us any drums they might find, which they did, in return for the nylon chutes (which local seamstresses and homemakers would put to good use) and a share of the food. That night, we had another party, except at this one, everyone was dressed in a new American uniform of his choice: Navy, Army, or Marine. The next day brought another three lumbering aerial giants—from the Marianas Islands, it turned out. Again, the local Japanese residents helped us, amid much bowing, collect the aerial bounty. By now, the camp was beginning to look like an oil refinery, with unopened 60-gallon oil drums stacked everywhere. When the daily ritual was repeated the day after that, some of the parachute lines snapped in the high winds, and the oil drums fell like giant rocks. Several hit the camp, went through the roofs of huts, hit the concrete floors and exploded. One was packed with canned peaches, and I don’t have to describe what the hut looked like. There were several very near-misses on our men, Japanese personnel and houses in the nearby village. When the next drop generated a similar result, I looked up to see that I was right under a cloud of falling 60-gallon oil drums. It was a terrifying moment. And I imagined the bizarre idea of surviving the enemy, surviving imprisonment, and then dying thanks to the kindness of well-meaning American pilots. Excerpts from a surviving biographical monograph on former camp commander Masake Naganuma We now had tons of food and supplies—enough for months, and more was arriving. The camp had begun to look as if it had been shelled by artillery. So we painted two words on the roof: NO MORE! The next day, the big friends came from the Marianas and, as we watched from the safety of a nearby tunnel, they circled the camp and, without opening their bay doors, flew back out to sea, firing off red rockets to show they’d received the message. It was a surreal scene. But it didn’t distract us from the fact that the generous and timely American response saved many of our lives. In the days that followed the drum showers, we settled down to caring for our sick and to some serious eating. Thanks to the US supplies, we began to gain a pound a day. The American generosity was especially notable given that few of the prisoners at Ohashi were American. Almost all were Canadian, Dutch, or British. At about this time, I decided to go back to the nearby mine where we’d worked as prisoner laborers. I wanted to say goodbye to the foreman of the machine shop, a grandfatherly man who’d called me hanchō (squad leader), and had been as kind to me as the brutal rules of the country’s military dictatorship permitted. It was both joyous and sad. We were happy that the war was over, yet sad at the knowledge that this would be our last meeting. I promised him that I would take his earnest advice and return to school as soon as I got home. “Hanchō, you go Canada now,” he said. Photo of mine workshop at Ohashi prison camp, where many POWs worked I later learned that about three million Japanese soldiers and civilians lost their lives in the war. Millions more were left wounded. The country had been hit with two atomic bombs. Whole cities had been gutted by fire. At every level, the war had been an unmitigated disaster for Japan. Its people had become cannon fodder in a cruel and pointless project to conquer East Asia. My fellow ex-POWs and I visited the camp graveyard, and said one last goodbye to our comrades who’d found their last resting place so far from home. It was an unjust reward for such brave young men. And it was then that tears I couldn’t control welled up in my eyes and streamed down my cheeks.  On September 14th, 30 days after Emperor Hirohito had publicly announced Japan’s surrender, a naval airplane flew in from the sea and dropped a note to inform us that an American naval task force would evacuate us on the following day. Sure enough, on September 15th, landing craft beached themselves and hastily disgorged a force of Marines. Their motorized column sped inland to the Ohashi camp, led by a Marine colonel and armed to the teeth. These were veterans of the long Pacific campaign. They’d survived many terrible encounters with the Japanese in their westward campaign across the Pacific, and they looked the part. After our captain saluted the colonel, they embraced, and the colonel told us how he planned to evacuate us, giving specific orders as to how it was all to be accomplished. Interpreter Hiroe Iwashita, remembered fondly by many prisoners After he issued his orders, the Colonel asked, “Are there any questions?” Our captain said, “Yes, I have one. Sir. What in the hell took you so long to get here?” That at least brought a smile to those tough, weather-beaten Marine faces. Following the Colonel’s instructions, we mounted up, said sayonara to Ohashi and, after almost four years of imprisonment, began the glorious journey home to our various loved ones. I was in the last vehicle that left the camp that day. And as we departed, I observed a compound that was now completely empty—save for one forlorn figure, who’d emerged from his office and now stood at the center of a camp that once held 400 men. It was Lieutenant Zenkichi. THEN US PILOTS SAVED MY LIFE SOURCE: QUILLETTE (CANADIAN) CANADA, HISTORY, TOP STORIES Published on August 15, 2020 George MacDonell was born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1922. He served in the Royal Rifles of Canada, which deployed to Hong Kong in 1941 as part of C-Force, shortly before Hong Kong’s capture by the Japanese army. |

Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|