|

By Dick Martin The Japanese had a much more difficult situation fueling their war machine in the Pacific Theatre than the Germans did in the Atlantic Theatre. The distances were much greater between military objectives and sources of fuel. You could fit ten Atlantic Theatres into one Pacific Theatre. The attack on Pearl Harbor was indirectly caused by the Japanese thirst for oil. We had been the primary source of oil for the Japanese before the war. Because of their military actions and atrocities in China and Manchuria, the US cut them off as their source of oil. Consequently, they felt that to realize their desires for dominating what they called, “The Japanese Co-Prosperity Sphere” (most of the Pacific west of Hawaii) they needed oil from SE Asia and they felt that the 7th Fleet, moored at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands, was all that stood between them and oil independence. Consequently, on December 7, 1941, “a day that would live in infamy,” their Naval Armada conducted a sneak air attack on the 7th Fleet and other US military institutions located in Hawaii. Luckily for the US, all of their carriers were absent as they were out to sea hunting submarines. Still they sank most of the ships still anchored at Pearl Harbor and killed over 2000 US military personel. Not given as much attention as the attack on Pearl Harbor, but perhaps even more important, was what happened thousands of miles away. Japanese planes destroyed most of MacArthur’s planes in the Philippines. Incredibly, they were caught on the ground even after he had been alerted by the Pearl Harbor fiasco. At this point, the Japanese had a clear route to oil in SE Asia and Indonesia. Realizing that the Japanese were after oil in the area, most of the wells were blown up or plugged with cement. Neither action was much more than an inconvenience to the Japanese and it took them little time to get the wells producing again. The overconfident Japanese saw a hookup with Germany, its ally, as a next step in their successes. Destroying America’s interest at Midway Island and a knockout blow to the Hawaiian Islands would destroy the 7th Fleet as an effective fighting force. However, they did not realize how quickly Pearl Harbor had recovered from their attack and did not realize the Americans had cracked their code. Consequently, the US knew their objective was Midway and had the resources there waiting for them and delivered a decisive blow by sinking four aircraft carriers while losing only one of their own. About the same time, the American Marines were delivering a decisive blow to the Japanese at Guadalcanal. These defeats and the success of US submarines sinking oil tankers in what the Japanese called “The Southern Zone,” were influencing strategic planning and were making it very difficult for the Japanese to get oil out of Indonesia and SE Asia. By mid-1945, all of their tankers attempting to bring oil out of SE Asia were sunk by US submarines. Japan’s shortage caused rationing in Japan, wild ideas for producing oil, and failed attempts at synthesizing oil. None worked or produced enough oil to be strategically worthwhile. The shortage of oil eventually caused the Japanese Navy’s final defeat as an effective fighting force in the Leyte Gulf. Like the Wehrmacht’s inability to fuel its war machine in Europe being a major factor in its demise, the Japanese were unable to fuel their planes and ships in the Pacific signaled their demise. For a much more thorough discussion of the effect of oil shortages on the Japanese, please see “The Prize” by Daniel Yergen pages 351 to 367. By Dick Martin In 1976, I entered the oil business, working for my uncle, buying oil and gas leases in the Catskills of New York. Fast forward 42 years until today and, for health reasons, I believe I have finally retired; although people in the oil business don’t really ever retire. The next deal may be just around the corner. The oil industry has a rich history of boom and bust cycles. It is full of characters such as John D Rockefeller, Henri Dieterding, Walter Teagle, H L Hunt, Dad Joiner, and more recently, Harold Ham, Aubrey McClendon, and George Mitchell. They all had one thing in common: They were willing to risk it all on an idea they believed in, no matter how risky it was. I call all of them CBs. I will let the viewer guess what that is an abbreviation for. I believe these last three people are responsible for America’s energy independence, something I did not believe we would ever see.

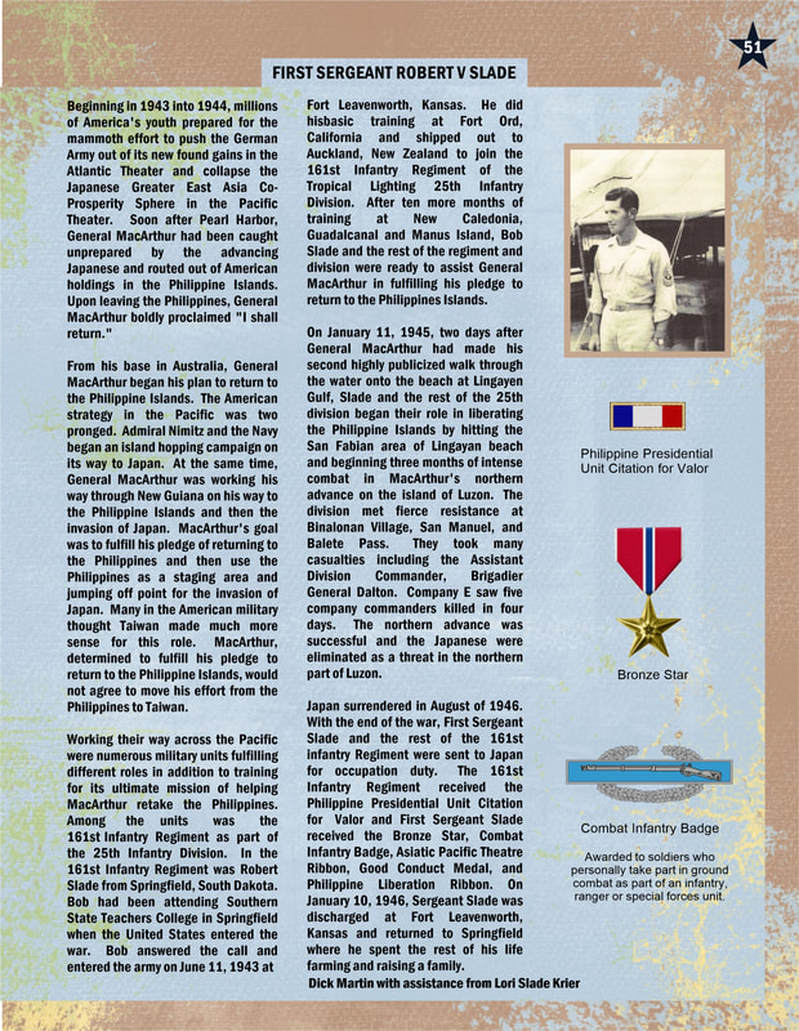

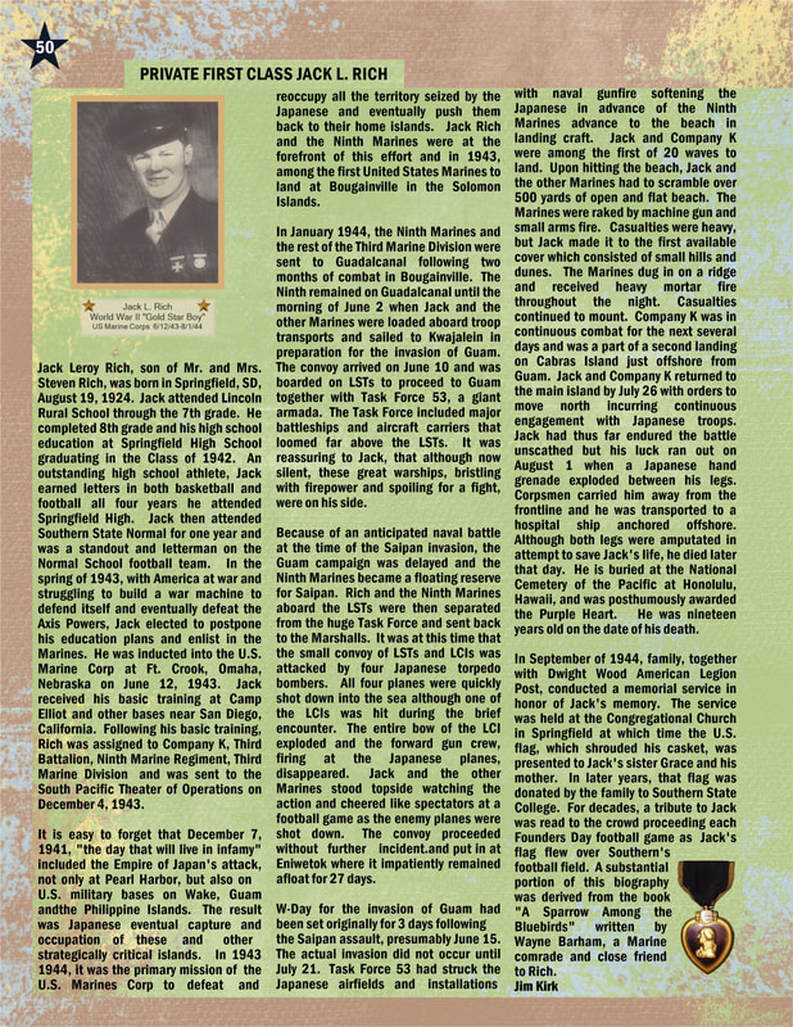

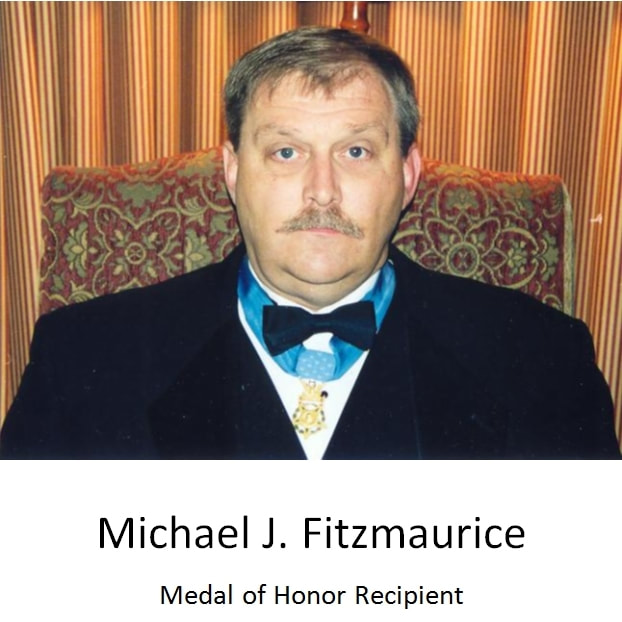

If one is interested in the history of the oil industry there are two books that are must reads: “The Prize” by Daniel Yergen and “The Frackers” by Gregory Zuckerman. I have read ”The Frackers” twice and am reading “The Prize” for the second time. The Prize covers the oil industry from the beginning until 1970 and “The Frackers” (has nothing to do with the fracking controversy) covers the industry from 1970 to a few years ago. I just finished the section of “The Prize” that covers WWII. Up until I read this section again, I had no idea how much of Hitler’s war efforts and overall plans depended on the production of natural or synthetic oil. Its military plans were influenced primarily by securing existing petroleum reserves in France and Russia and capturing the production in Ploesti or the Caucuses oil fields in Russia and Rumania. Germany’s best general, Irwin Rommel, was stopped cold in North Africa and Hitler’s counter-attack in the Battle of the Bulge was stopped just short of its goal of Antwerp, Belgium, both because its tanks ran out of fuel. In Russia, Hitler’s generals could not escape encirclement and annihilation because of lost mobility due to a lack of petroleum. In 1940 Germany produced 72,000 barrels of synthetic oil a day, and in 1943, at Hitler’s peak, Germany was producing 124,000 barrels a day. From 1943 till the end of the war in 1945, due to Allied bombing, its production declined precipitously along with its military successes. By the end of the war, Germany was producing only a few thousand barrels of oil a day. It had planes and tanks stranded all over Europe due to a shortage of oil. If there had not been a shortage of oil to fuel the Luftwaffe, tanks and the rest of Hitler’s war machine, WWII probably would not have ended in 1945. I don’t believe historians have given oil its rightful place in the major reasons Hitler did not realize his dreams of an Aryan World. The Japanese faced the same situation in the Pacific that the Germans faced in Europe, ie their shortage of oil prevented military successes. Due to the industrial might of the United States, it is generally agreed that Germany’s and Japan’s fate was sealed the first day of the war. It can be more specifically concluded that their inability to satisfy their demand for oil to fuel their military might doomed them from the beginning. For a more thorough discussion of the lack of oil dilemma faced by Hitler and his Wehrmacht, please check out “The Prize” by Daniel Yergen, pages 328 to 350. Next, I will summarize and discuss the Japanese dilemma in the Pacific in fueling their war machine. The highest military medal awarded for bravery is the Medal of Honor. See other parts of this web site for a discussion of that medal and other medals for bravery awarded to Springfield veterans. I believe Springfield has one or two veterans with the second highest award for bravery and two or three with the third highest award. There have been nine South Dakotans awarded the Medal of Honor. They are Captain Willibald C. Bianchi, General Patrick H. Brady, Specialist Four Michael J. Fitzmaurice, Captain Joe J. Foss, Master Sergeant Woodrow W. Keeble, Private First Class Herbert A. Littleton, Captain Arlo L. Olson, Brigadier General Charles D. Roberts, Colonel Leo K. Thorsness. Thanks to Jim Hornstra we have write-ups on all nine and we will periodically publish one in our Sunday Feature section of this web site. Dick Martin Submitted by Jim Hornstra from the South Dakota archives Call it a difference of opinion, or a matter of interpretation. Call it whatever you wish, but the plain fact is that the United States Army and Michael J. Fitzmaurice do not seem to be of one mind when it comes to the events of March 23, 1971. For its part, the Army uses phrases like, “conspicuous gallantry,” and, “above and beyond the call of duty,” to describe what Fitzmaurice did when North Vietnamese soldiers attacked his unit’s position at Khesanh, Vietnam. They awarded him the Congressional Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest military decoration, for his actions. Fitzmaurice does not dispute the Army’s account of that night, but the self-effacing Hartford man does not seem convinced that his actions rose to the level of gallantry, either. He was just being a good soldier. Fighting as he had been trained, defending his post and helping the rest of his outfit live to see another day. He is quietly proud of that. As for earning the medal itself, there’s a very simple explanation for that. “I just got lucky,” he said. General William Westmoreland once compared the country of Vietnam to a don ganh — the pole that is carried across a man’s shoulders, with baskets suspended from either end — which has been used to carry burdens in Asia for thousands of years. Vietnam’s two most important regions, the Mekong River delta in the south and the Red River basin of the north, comprise the baskets; a slender strip of land hugging the South China Sea, the pole, connects these two. Near the center of that pole is the 17th Parallel, chosen as the dividing line between North and South Vietnam when the country was partitioned in 1954. Just south of that line, in the mountainous jungle near Laos, lies the village of Khesanh. Early in 1968, Khesanh was added to the roll of battle names that will resonate down through American military history when North Vietnamese troops attacked and surrounded the U.S. base there. What had been a relatively quiet, obscure outpost suddenly loomed large when it became the focal point of a 77-day siege that reduced the defending Marines’ existence to a hellish struggle for survival. A world away from Khesanh, in Iroquois, South Dakota, Michael Fitzmaurice was a junior in high school. By his own account, he did not pay much attention to the war back then. Following graduation in 1969 he and several classmates enlisted in the Army — he was the only one who ended up serving in Vietnam — and he left for boot camp on Halloween. By the following May, Fitzmaurice was in the war zone, assigned to the Second Squadron, 17th Cavalry, 101st Airborne Division. As a helicopter borne unit, the Second was a reactionary force: they were deployed to places where combat was already going on and another outfit needed help, or to help rescue the crews of downed aircraft who were under attack. At other times they were assigned to, “fly in and look things over,” as Fitzmaurice laconically described it, searching bunker complexes and other suspect areas. Fitzmaurice was in Vietnam for two months prior to the action at Khesanh. “I don’t know what a lot is,” said Fitzmaurice when asked how extensive his combat experience was during that time. “But we got shot at quite a few times. Nothing as serious as that night, though.” Fitzmaurice as a soldier Shortly after the battle of Khesanh in 1968, American forces had abandoned the base. When the decision was made to go into Laos three years later, however, the airstrip was again needed to support raids against the Ho Chi Minh trail, just across the border. Fitzmaurice’s unit was assigned to guard the airstrip. “We thought it was going to be good duty,” he said, grinning, but reality was quite different. “We were getting rocketed every night ... there were ground assaults.” On the night of March 23, the North Vietnamese attacked once again. A company-sized force broke through the perimeter to where the helicopters were parked, “and things kind of went downhill from there,” said Fitzmaurice. “I had just gotten off guard duty when they started coming in. I was wide awake,” he recalls. Fitzmaurice was in a bunker with three buddies when three hand grenades landed in their trench. “I threw two of them out, and covered the third with a flak jacket. It blew me up out of the hole, and that’s about it. I just stayed out there and finished up the fighting.” Fitzmaurice’s account is remarkable for its brevity, but the Army’s version of events is more illuminating. “Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice and three fellow soldiers were occupying a bunker when a company of North Vietnamese sappers infiltrated the area. At the onset of the attack Fitzmaurice observed three explosive charges which had been thrown into the bunker by the enemy. Realizing the imminent danger to his comrades, and with complete disregard for his personal safety, he hurled two of the charges out of the bunker. He then threw his flak vest and himself over the remaining charge. By this courageous act he absorbed the blast and shielded his fellow soldiers. “Although suffering from serious multiple wounds and partial loss of sight, he charged out of the bunker and engaged the enemy until his rifle was damaged by the blast of an enemy hand grenade. While in search of another weapon, Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice encountered and overcame an enemy sapper in hand-to-hand combat. Having obtained another weapon, he returned to his original fighting position and inflicted additional casualties on the attacking enemy. Although seriously wounded, Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice refused to be medically evacuated, preferring to remain at his post. Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice’s extraordinary heroism in action at the risk of his life contributed significantly to the successful defense of his position and resulted in saving the lives of a number of his fellow soldiers. These acts of heroism go above and beyond the call of duty, are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect great credit on Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice and the U.S. Army.” One of the three other soldiers in the bunker that night was Billy Fowler, from Georgia, Fitzmaurice’s closest friend in the whole outfit. “[Michael] was the first guy I met when I got over there,” Fowler remembered. “We just hit it off. But everybody liked him. He was just a good soldier.” The explosion that tossed Fitzmaurice out of the bunker partially buried another soldier and Fowler, “but all I got was one little piece of shrapnel in my back, never even had to go to the hospital,” he said. In the confusion of the firefight they lost contact, but he and the others were pretty sure what had happened to Fitzmaurice. “We all thought he was dead.” When the fighting ended that morning about sunrise, Fitzmaurice finally consented to be evacuated, and spent the next 14 months in and out of hospitals. He had numerous shrapnel wounds, one eye got dislocated, and the force of the explosion had raised havoc with his eardrums; doctors could not get the right side to heal properly for a long time. Fitzmaurice wears hearing aids in both ears today, which remarkably are his only ailments attributable to that night. Fitzmaurice does not know who initiated the Medal of Honor process. He was back in South Dakota, working at a packing plant in Huron, when he received notification. He was married by that time, so he and his wife, Patty, plus two brothers and his parents, were invited to the White House on October 15, 1973. There he received his medal from President Richard Nixon. “That was pretty interesting,” said Fitzmaurice. As the only Medal of Honor winner living in the state, Fitzmaurice is a somewhat reluctant celebrity. South Dakota Public Broadcasting did a segment on him for its Dakota Stories program, and he frequently gets requests for souvenirs or mementos from all over. He has been honored by the state twice. In 1996, 25 years to the day after the action at Khesanh, Gov. Bill Janklow presented Fitzmaurice with a special license plate, CMH1, in recognition of his accomplishment, and in October of 1998 the state Veterans Home in Hot Springs was renamed in his honor. Fitzmaurice works at the Royal C. Johnson Veterans Administration Hospital in Sioux Falls as a plumber these days. Seeing him walk the halls with a problem faucet in hand leads you to wonder: there were four men in the bunker the night those grenades landed. Michael Fitzmaurice acted, saving the others. Why him? Was it instinct? Exceptional courage? Something indefinable? Because of his genuinely humble nature, Michael Fitzmaurice is of little help in answering that question. “We were just trained to do what we had to do. We were all in this little hole. We weren’t going any place,” he said simply. If pressed, he will venture a little farther. “I was closest to [the charges]. I didn’t think about it. There are lots of things we wouldn’t do if we stopped to think about it.” Perhaps it is best for us all to leave his story there. Then we can believe that someday, if we find ourselves in a difficult situation, we might find within our hearts the capacity to be heroes, too. From, South Dakota Magazine |

Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|