|

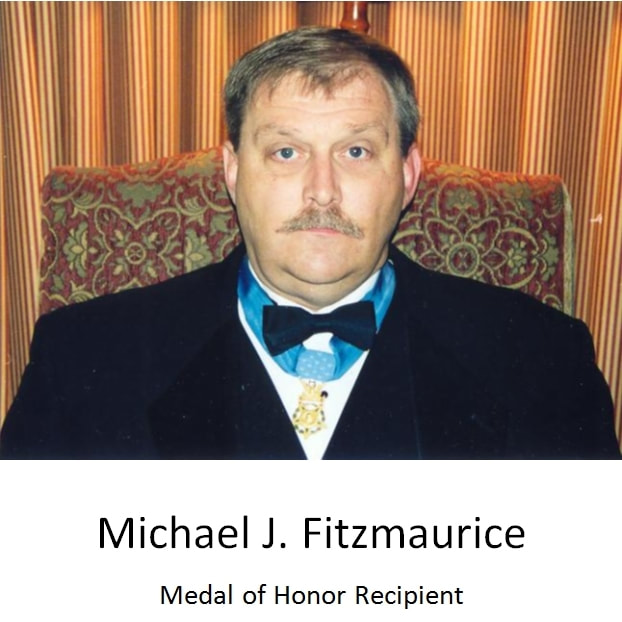

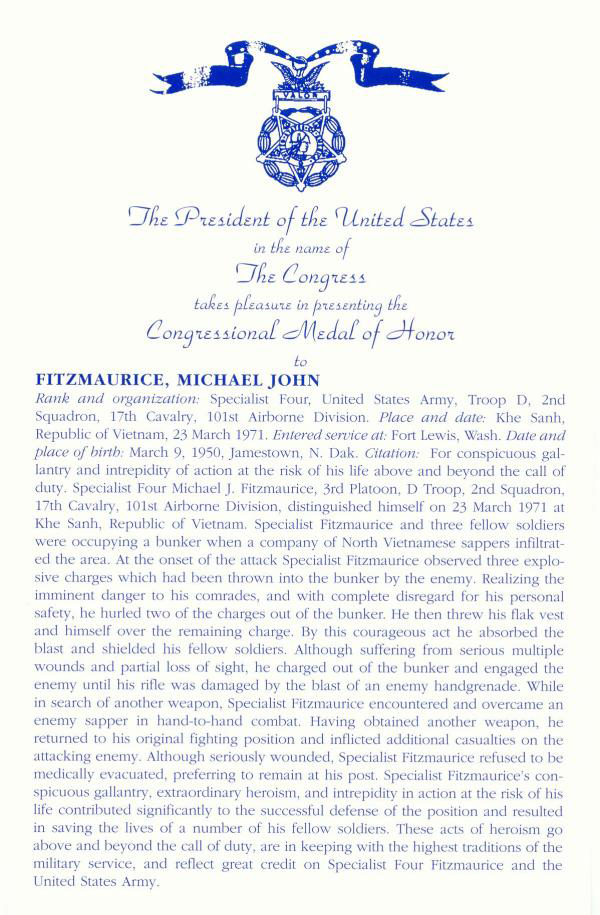

The highest military medal awarded for bravery is the Medal of Honor. See other parts of this web site for a discussion of that medal and other medals for bravery awarded to Springfield veterans. I believe Springfield has one or two veterans with the second highest award for bravery and two or three with the third highest award. There have been nine South Dakotans awarded the Medal of Honor. They are Captain Willibald C. Bianchi, General Patrick H. Brady, Specialist Four Michael J. Fitzmaurice, Captain Joe J. Foss, Master Sergeant Woodrow W. Keeble, Private First Class Herbert A. Littleton, Captain Arlo L. Olson, Brigadier General Charles D. Roberts, Colonel Leo K. Thorsness. Thanks to Jim Hornstra we have write-ups on all nine and we will periodically publish one in our Sunday Feature section of this web site. Dick Martin Submitted by Jim Hornstra from the South Dakota archives Call it a difference of opinion, or a matter of interpretation. Call it whatever you wish, but the plain fact is that the United States Army and Michael J. Fitzmaurice do not seem to be of one mind when it comes to the events of March 23, 1971. For its part, the Army uses phrases like, “conspicuous gallantry,” and, “above and beyond the call of duty,” to describe what Fitzmaurice did when North Vietnamese soldiers attacked his unit’s position at Khesanh, Vietnam. They awarded him the Congressional Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest military decoration, for his actions. Fitzmaurice does not dispute the Army’s account of that night, but the self-effacing Hartford man does not seem convinced that his actions rose to the level of gallantry, either. He was just being a good soldier. Fighting as he had been trained, defending his post and helping the rest of his outfit live to see another day. He is quietly proud of that. As for earning the medal itself, there’s a very simple explanation for that. “I just got lucky,” he said. General William Westmoreland once compared the country of Vietnam to a don ganh — the pole that is carried across a man’s shoulders, with baskets suspended from either end — which has been used to carry burdens in Asia for thousands of years. Vietnam’s two most important regions, the Mekong River delta in the south and the Red River basin of the north, comprise the baskets; a slender strip of land hugging the South China Sea, the pole, connects these two. Near the center of that pole is the 17th Parallel, chosen as the dividing line between North and South Vietnam when the country was partitioned in 1954. Just south of that line, in the mountainous jungle near Laos, lies the village of Khesanh. Early in 1968, Khesanh was added to the roll of battle names that will resonate down through American military history when North Vietnamese troops attacked and surrounded the U.S. base there. What had been a relatively quiet, obscure outpost suddenly loomed large when it became the focal point of a 77-day siege that reduced the defending Marines’ existence to a hellish struggle for survival. A world away from Khesanh, in Iroquois, South Dakota, Michael Fitzmaurice was a junior in high school. By his own account, he did not pay much attention to the war back then. Following graduation in 1969 he and several classmates enlisted in the Army — he was the only one who ended up serving in Vietnam — and he left for boot camp on Halloween. By the following May, Fitzmaurice was in the war zone, assigned to the Second Squadron, 17th Cavalry, 101st Airborne Division. As a helicopter borne unit, the Second was a reactionary force: they were deployed to places where combat was already going on and another outfit needed help, or to help rescue the crews of downed aircraft who were under attack. At other times they were assigned to, “fly in and look things over,” as Fitzmaurice laconically described it, searching bunker complexes and other suspect areas. Fitzmaurice was in Vietnam for two months prior to the action at Khesanh. “I don’t know what a lot is,” said Fitzmaurice when asked how extensive his combat experience was during that time. “But we got shot at quite a few times. Nothing as serious as that night, though.” Fitzmaurice as a soldier Shortly after the battle of Khesanh in 1968, American forces had abandoned the base. When the decision was made to go into Laos three years later, however, the airstrip was again needed to support raids against the Ho Chi Minh trail, just across the border. Fitzmaurice’s unit was assigned to guard the airstrip. “We thought it was going to be good duty,” he said, grinning, but reality was quite different. “We were getting rocketed every night ... there were ground assaults.” On the night of March 23, the North Vietnamese attacked once again. A company-sized force broke through the perimeter to where the helicopters were parked, “and things kind of went downhill from there,” said Fitzmaurice. “I had just gotten off guard duty when they started coming in. I was wide awake,” he recalls. Fitzmaurice was in a bunker with three buddies when three hand grenades landed in their trench. “I threw two of them out, and covered the third with a flak jacket. It blew me up out of the hole, and that’s about it. I just stayed out there and finished up the fighting.” Fitzmaurice’s account is remarkable for its brevity, but the Army’s version of events is more illuminating. “Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice and three fellow soldiers were occupying a bunker when a company of North Vietnamese sappers infiltrated the area. At the onset of the attack Fitzmaurice observed three explosive charges which had been thrown into the bunker by the enemy. Realizing the imminent danger to his comrades, and with complete disregard for his personal safety, he hurled two of the charges out of the bunker. He then threw his flak vest and himself over the remaining charge. By this courageous act he absorbed the blast and shielded his fellow soldiers. “Although suffering from serious multiple wounds and partial loss of sight, he charged out of the bunker and engaged the enemy until his rifle was damaged by the blast of an enemy hand grenade. While in search of another weapon, Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice encountered and overcame an enemy sapper in hand-to-hand combat. Having obtained another weapon, he returned to his original fighting position and inflicted additional casualties on the attacking enemy. Although seriously wounded, Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice refused to be medically evacuated, preferring to remain at his post. Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice’s extraordinary heroism in action at the risk of his life contributed significantly to the successful defense of his position and resulted in saving the lives of a number of his fellow soldiers. These acts of heroism go above and beyond the call of duty, are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect great credit on Specialist Fourth Class Fitzmaurice and the U.S. Army.” One of the three other soldiers in the bunker that night was Billy Fowler, from Georgia, Fitzmaurice’s closest friend in the whole outfit. “[Michael] was the first guy I met when I got over there,” Fowler remembered. “We just hit it off. But everybody liked him. He was just a good soldier.” The explosion that tossed Fitzmaurice out of the bunker partially buried another soldier and Fowler, “but all I got was one little piece of shrapnel in my back, never even had to go to the hospital,” he said. In the confusion of the firefight they lost contact, but he and the others were pretty sure what had happened to Fitzmaurice. “We all thought he was dead.” When the fighting ended that morning about sunrise, Fitzmaurice finally consented to be evacuated, and spent the next 14 months in and out of hospitals. He had numerous shrapnel wounds, one eye got dislocated, and the force of the explosion had raised havoc with his eardrums; doctors could not get the right side to heal properly for a long time. Fitzmaurice wears hearing aids in both ears today, which remarkably are his only ailments attributable to that night. Fitzmaurice does not know who initiated the Medal of Honor process. He was back in South Dakota, working at a packing plant in Huron, when he received notification. He was married by that time, so he and his wife, Patty, plus two brothers and his parents, were invited to the White House on October 15, 1973. There he received his medal from President Richard Nixon. “That was pretty interesting,” said Fitzmaurice. As the only Medal of Honor winner living in the state, Fitzmaurice is a somewhat reluctant celebrity. South Dakota Public Broadcasting did a segment on him for its Dakota Stories program, and he frequently gets requests for souvenirs or mementos from all over. He has been honored by the state twice. In 1996, 25 years to the day after the action at Khesanh, Gov. Bill Janklow presented Fitzmaurice with a special license plate, CMH1, in recognition of his accomplishment, and in October of 1998 the state Veterans Home in Hot Springs was renamed in his honor. Fitzmaurice works at the Royal C. Johnson Veterans Administration Hospital in Sioux Falls as a plumber these days. Seeing him walk the halls with a problem faucet in hand leads you to wonder: there were four men in the bunker the night those grenades landed. Michael Fitzmaurice acted, saving the others. Why him? Was it instinct? Exceptional courage? Something indefinable? Because of his genuinely humble nature, Michael Fitzmaurice is of little help in answering that question. “We were just trained to do what we had to do. We were all in this little hole. We weren’t going any place,” he said simply. If pressed, he will venture a little farther. “I was closest to [the charges]. I didn’t think about it. There are lots of things we wouldn’t do if we stopped to think about it.” Perhaps it is best for us all to leave his story there. Then we can believe that someday, if we find ourselves in a difficult situation, we might find within our hearts the capacity to be heroes, too. From, South Dakota Magazine

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

October 2023

|